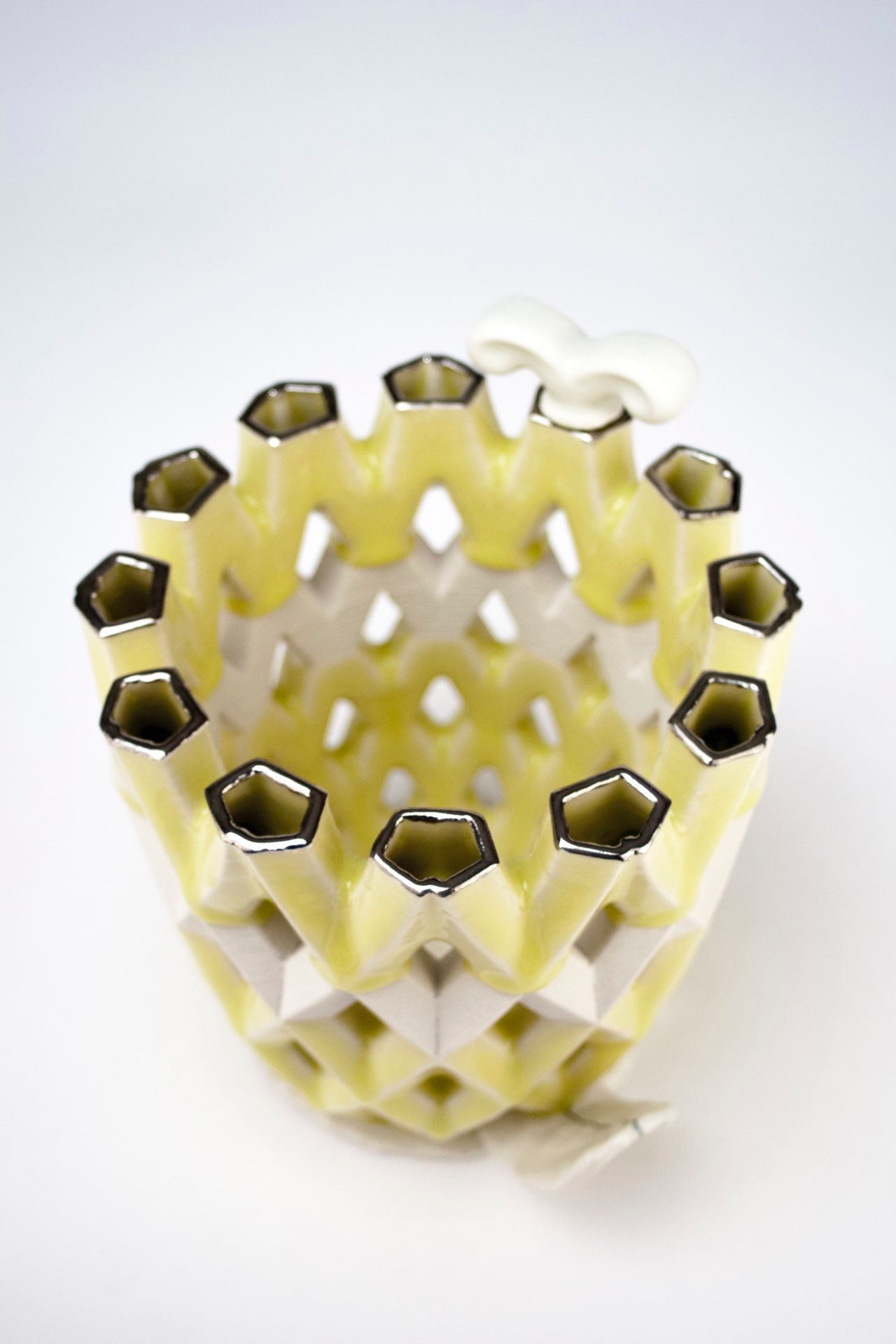

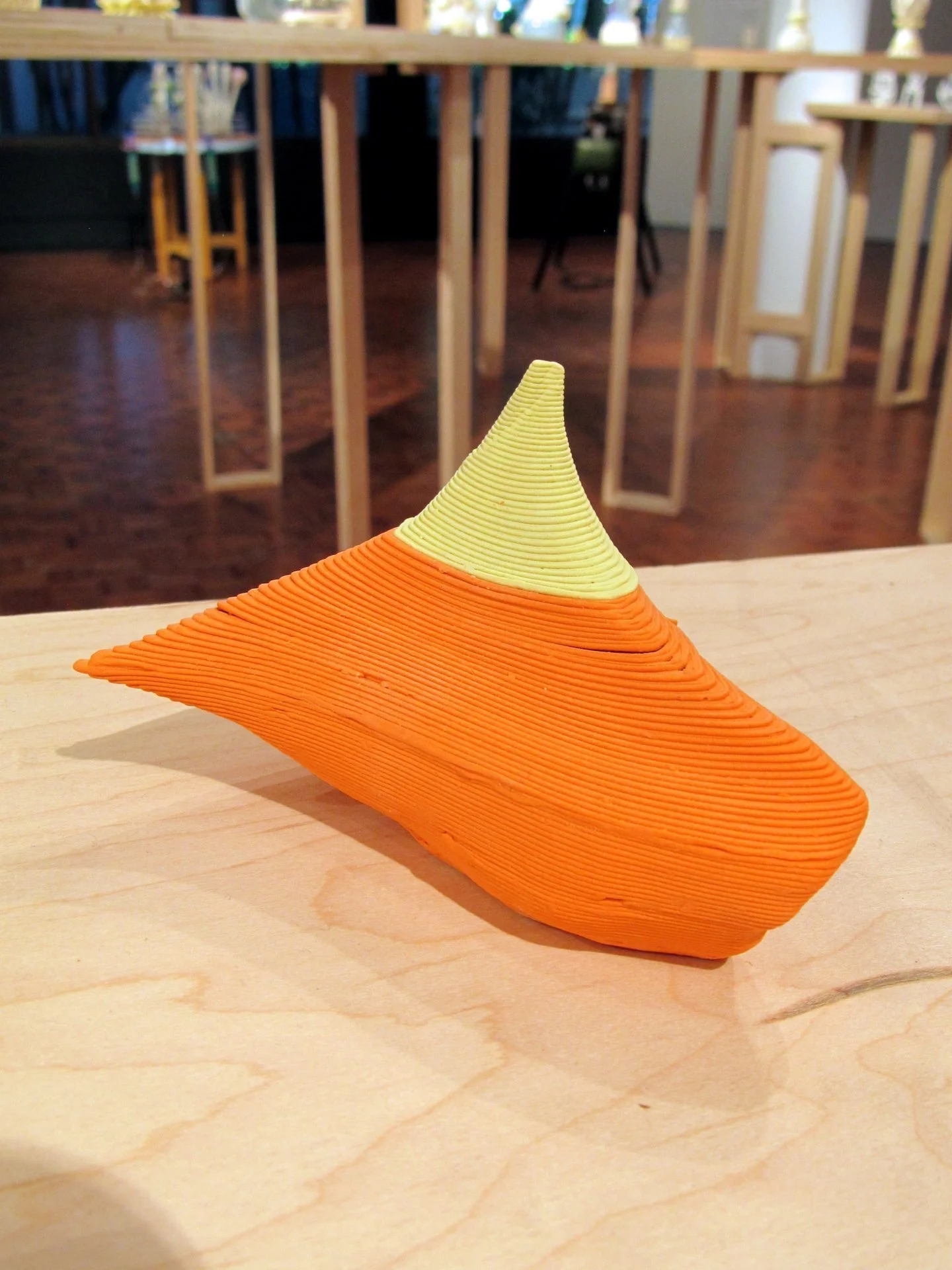

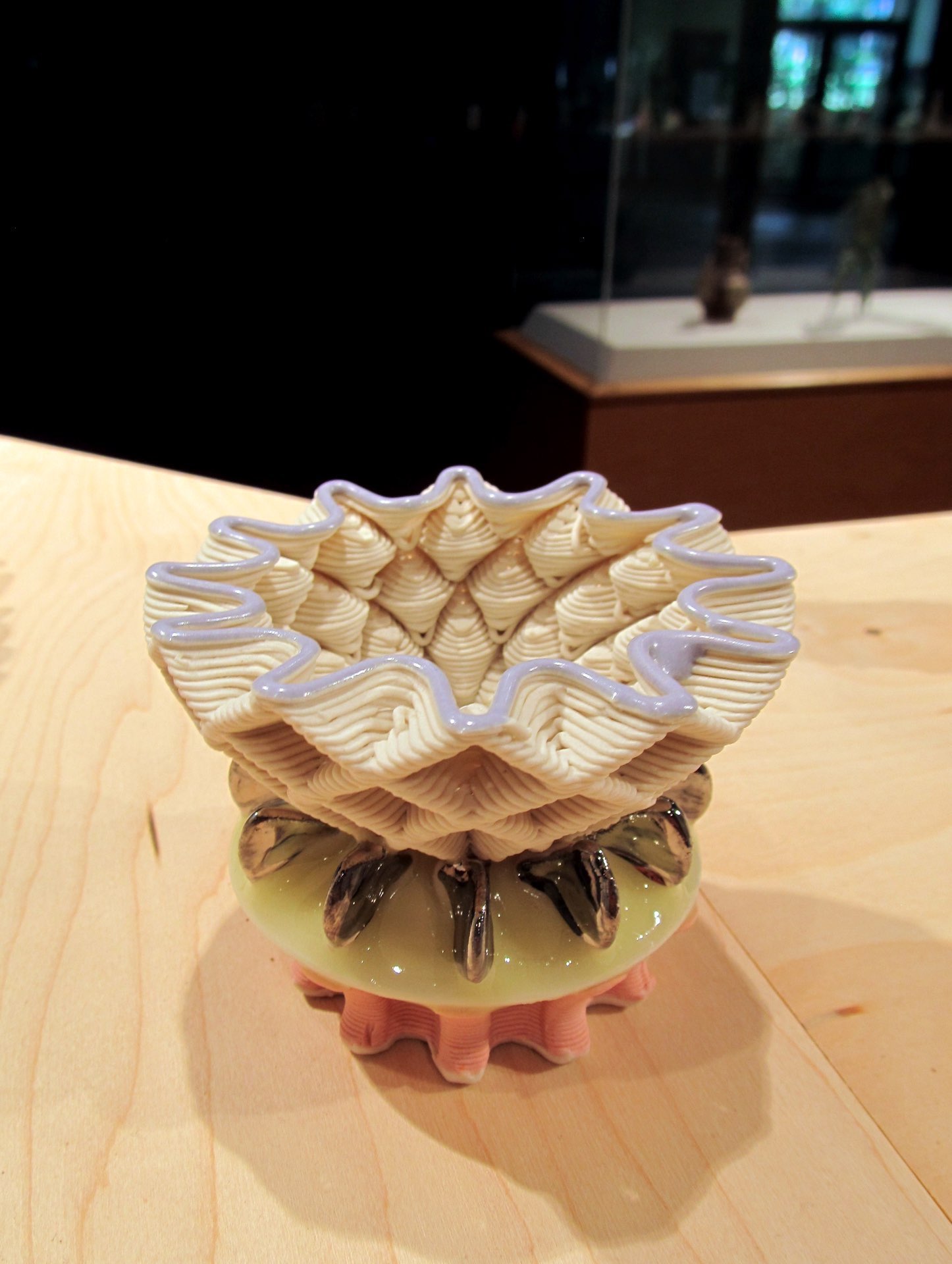

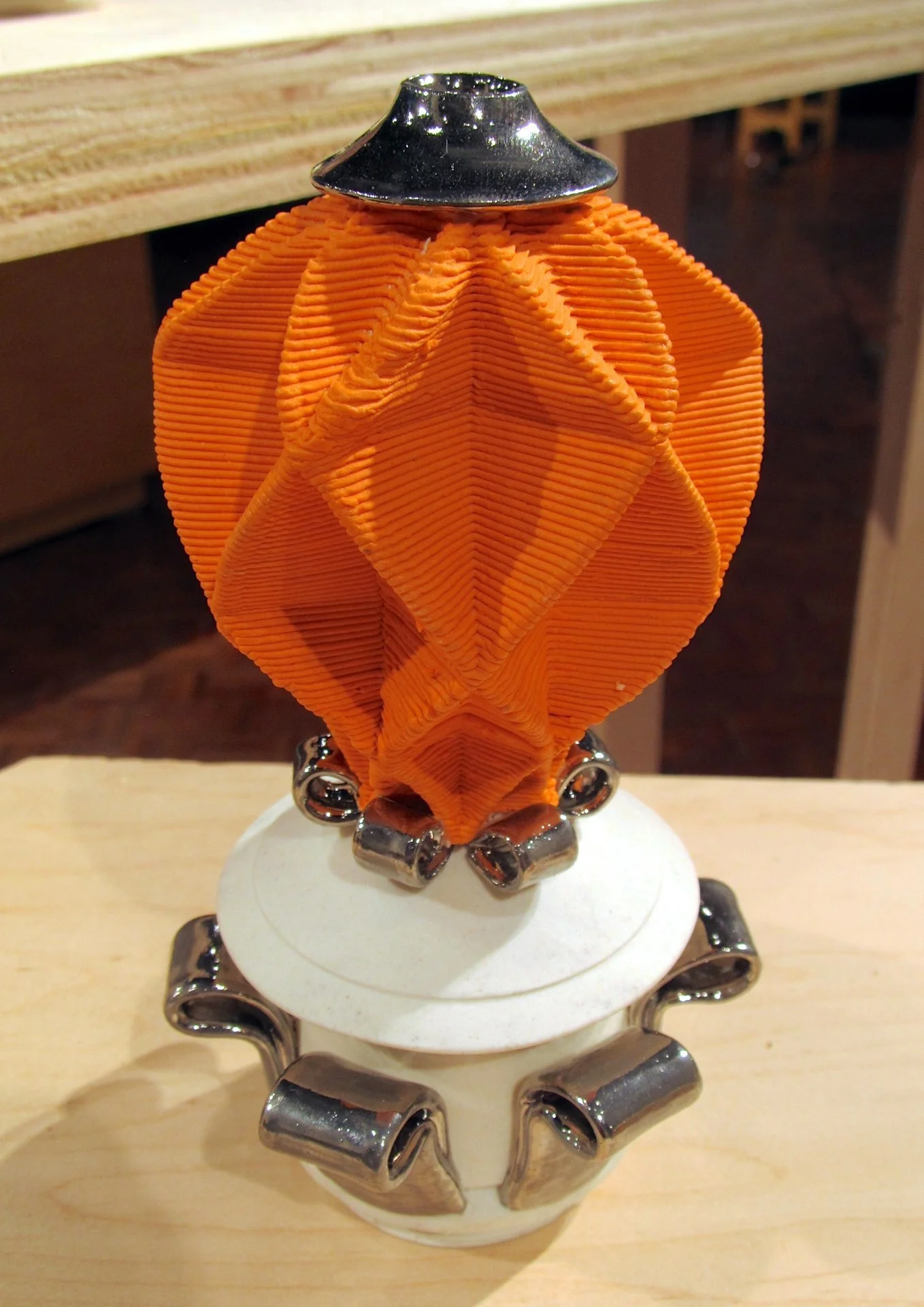

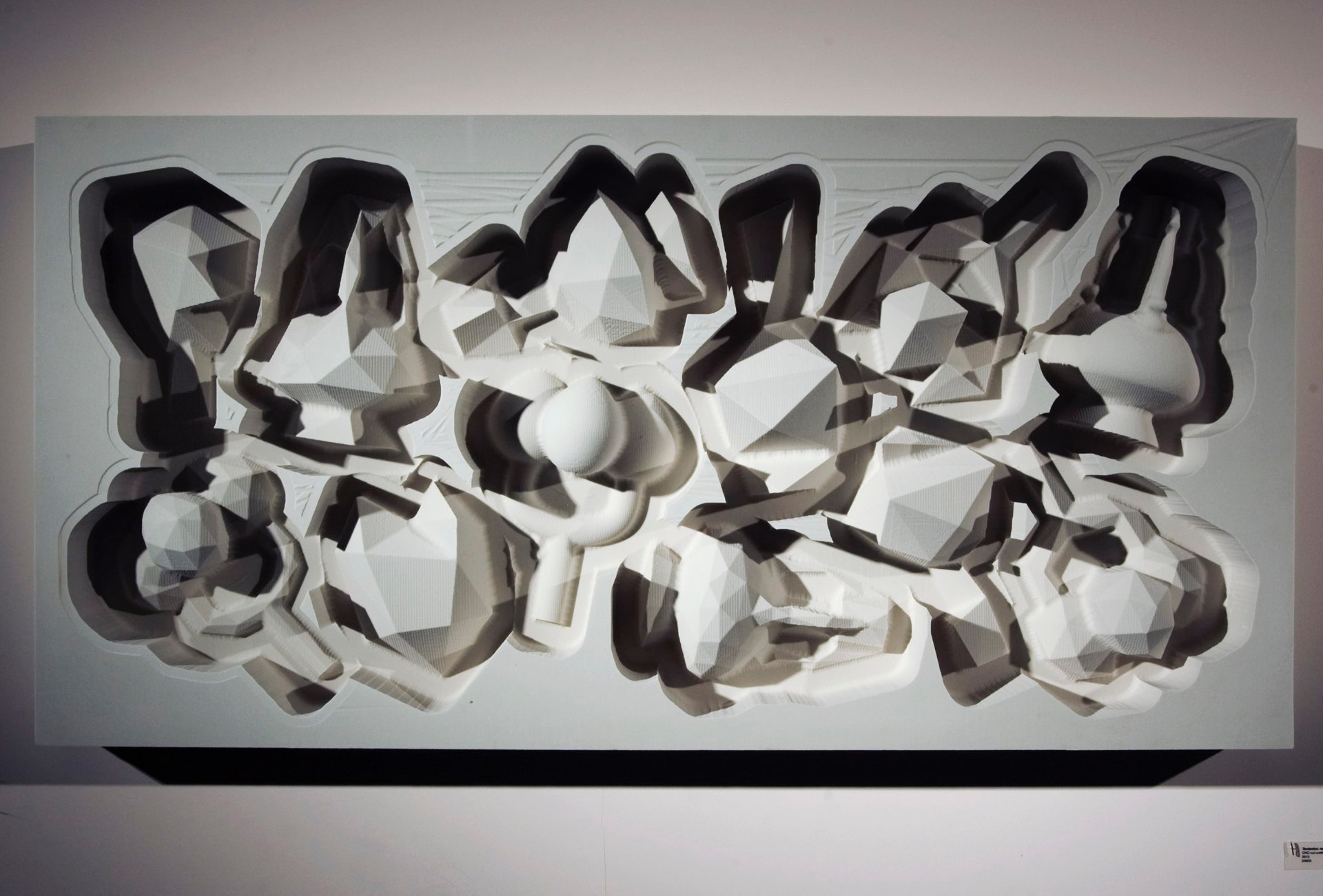

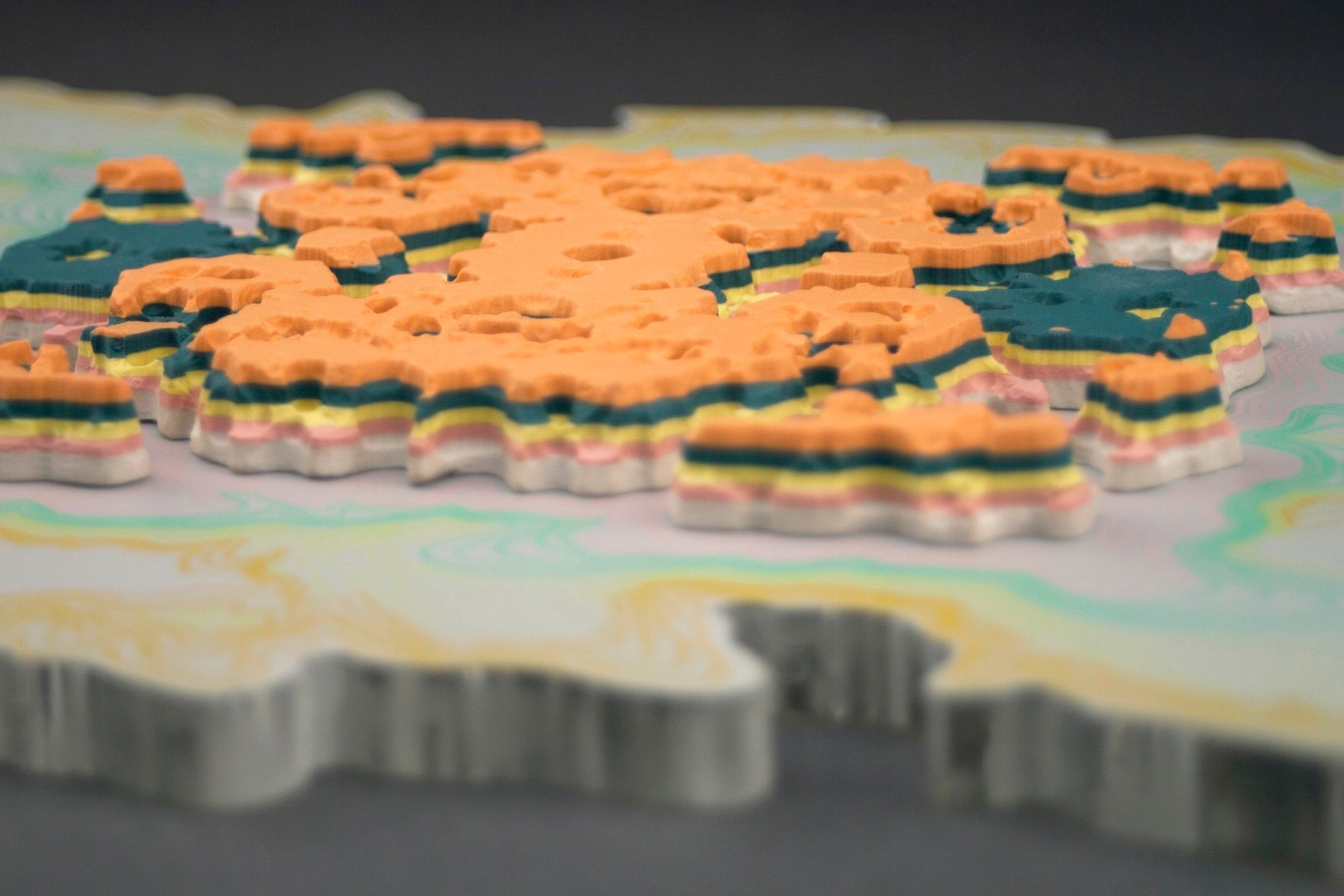

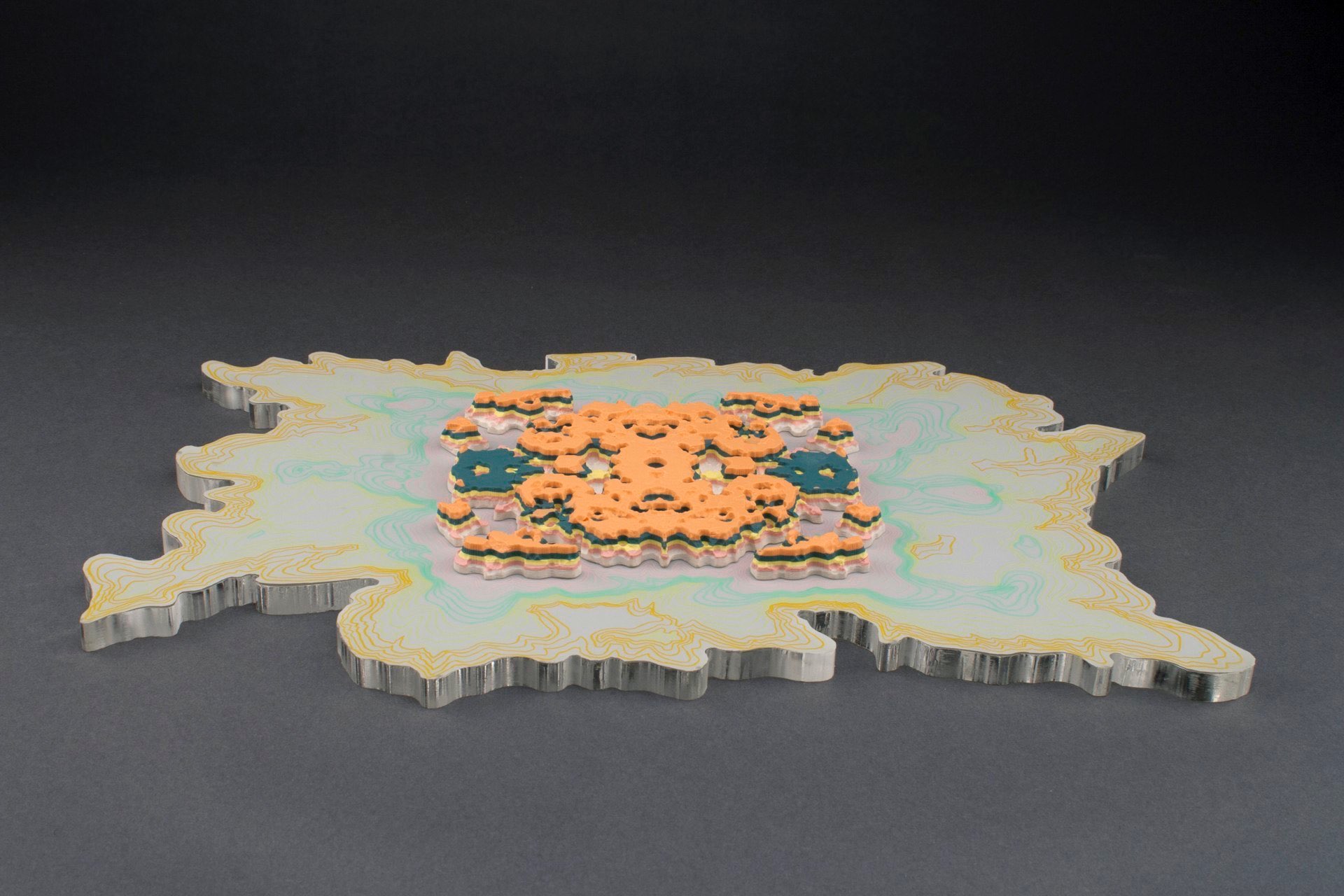

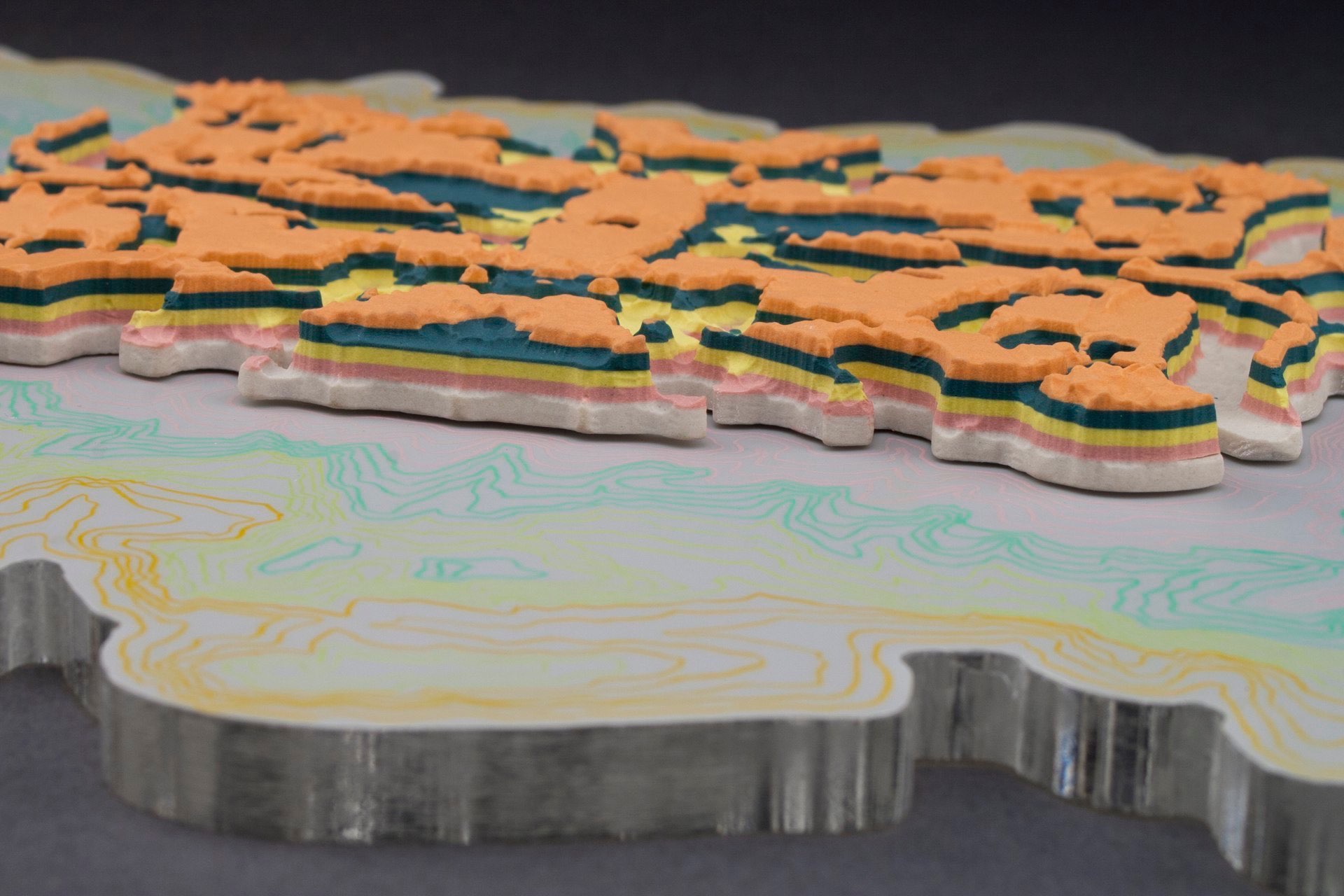

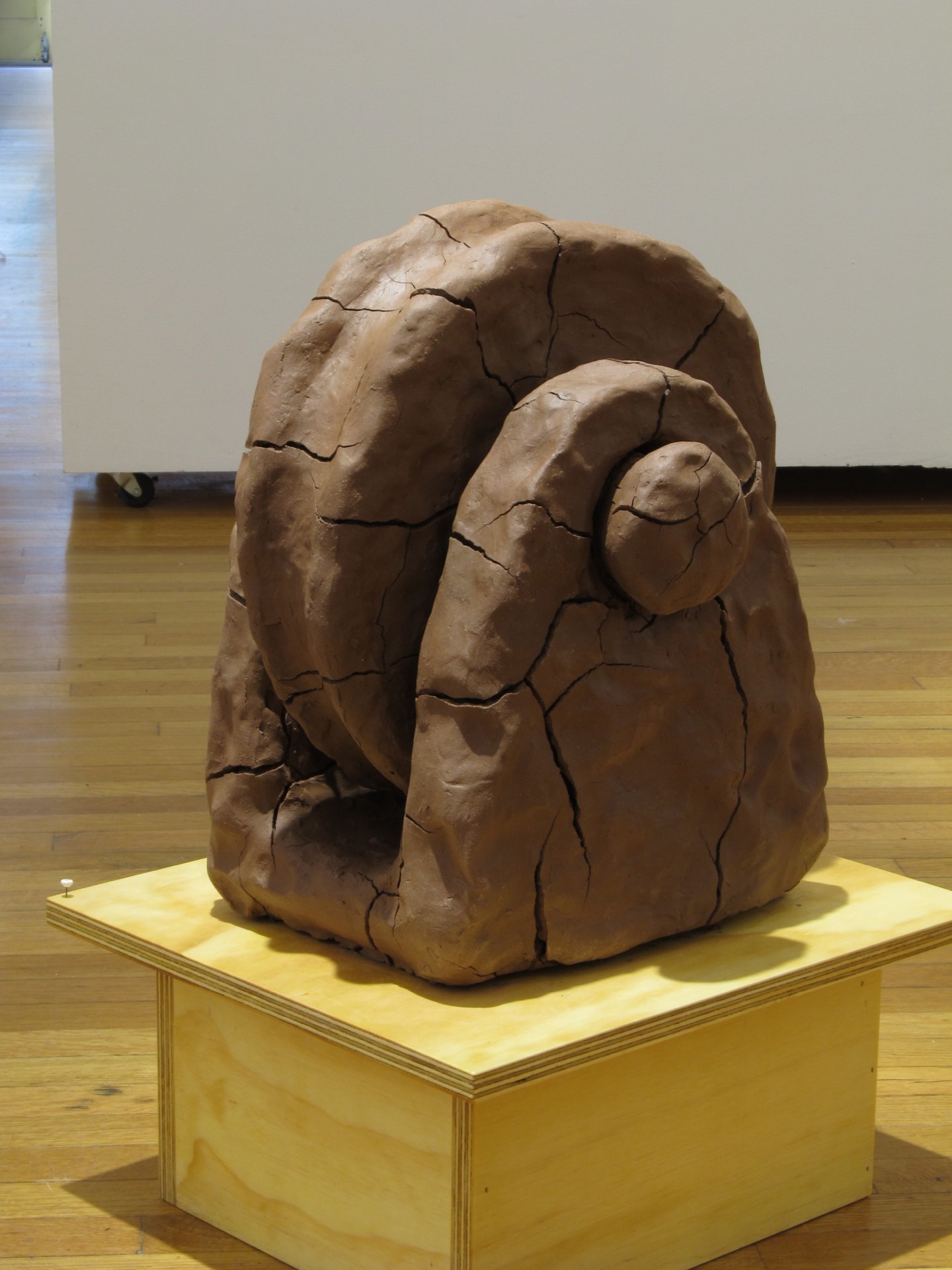

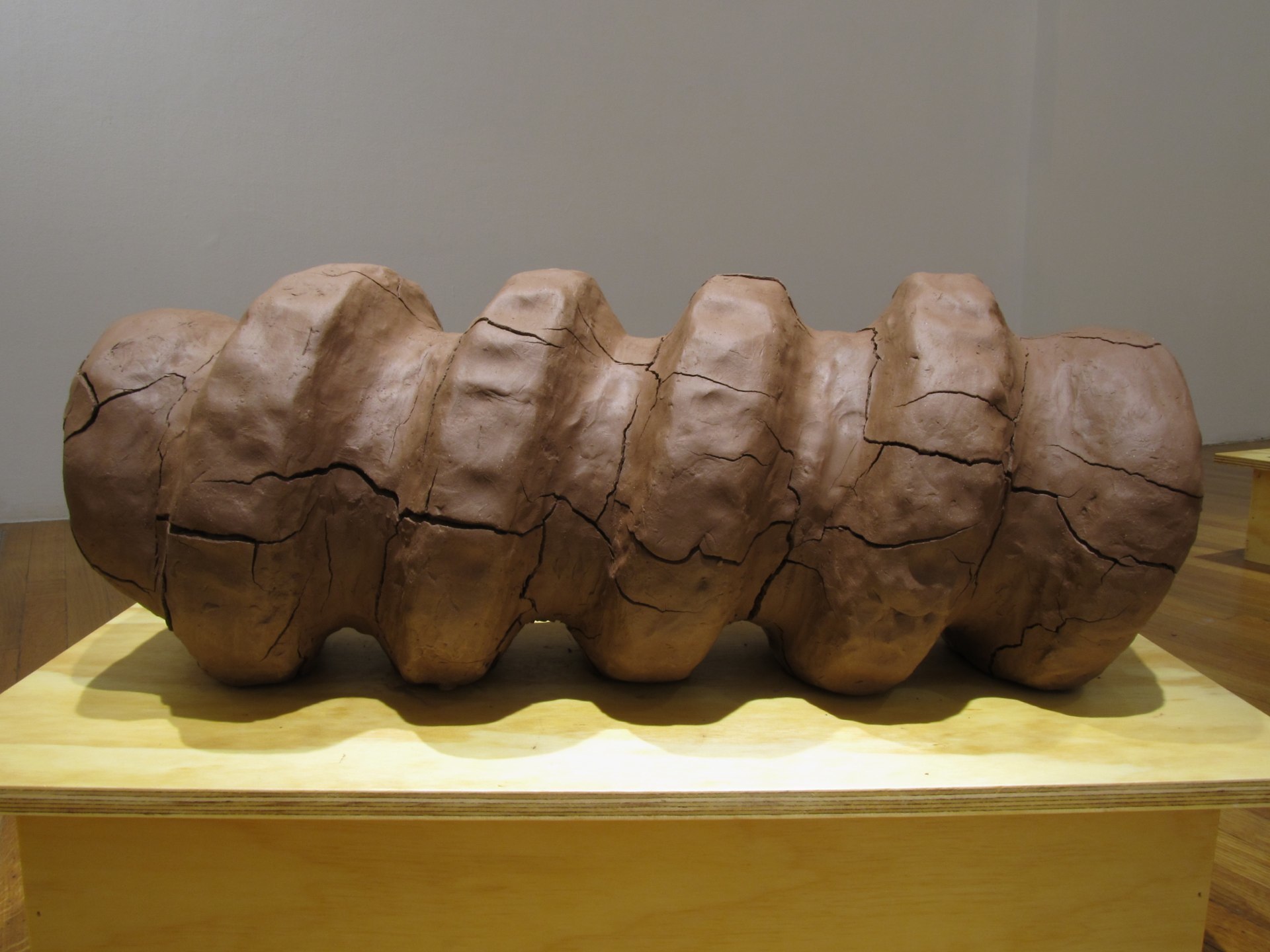

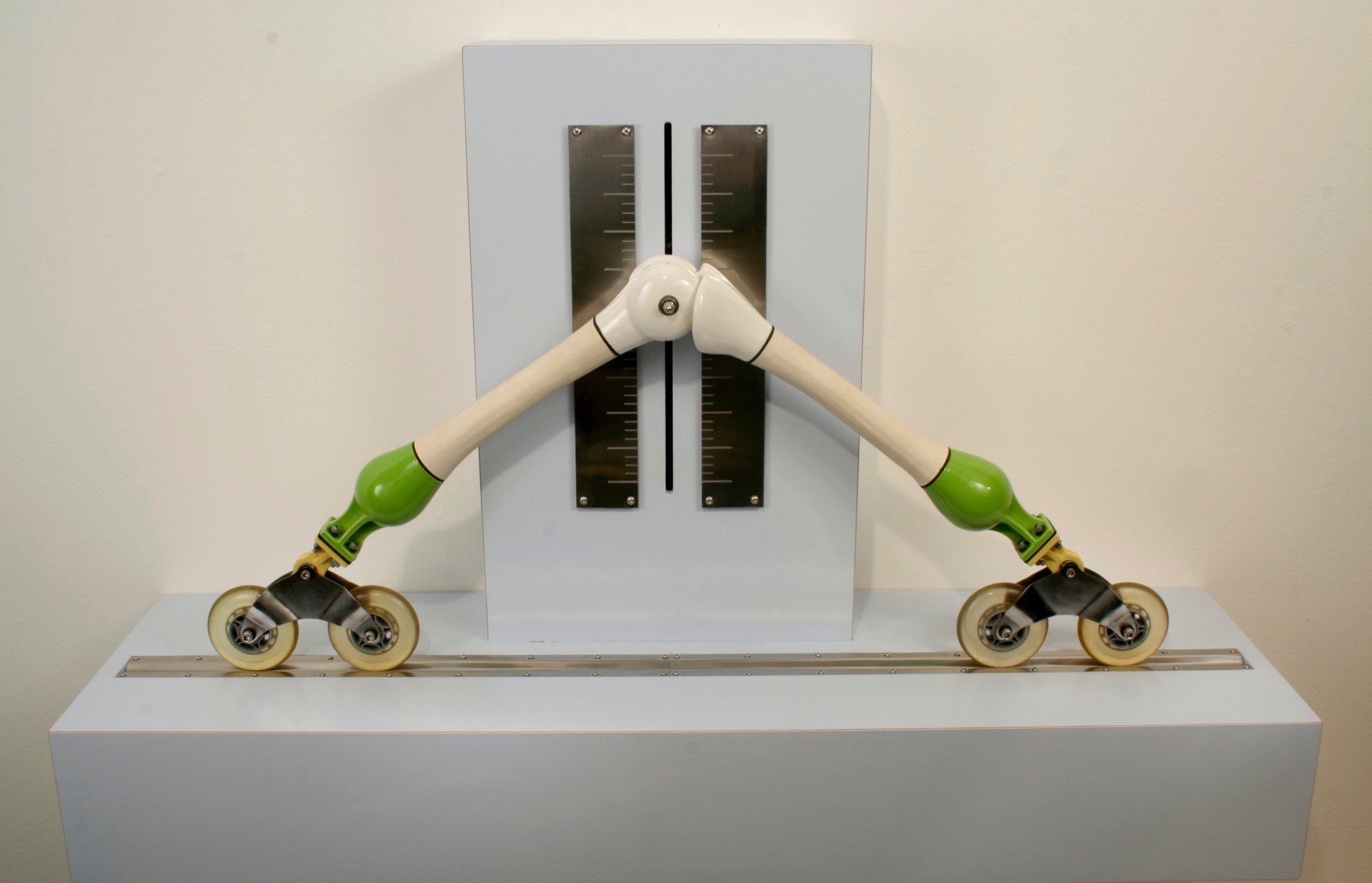

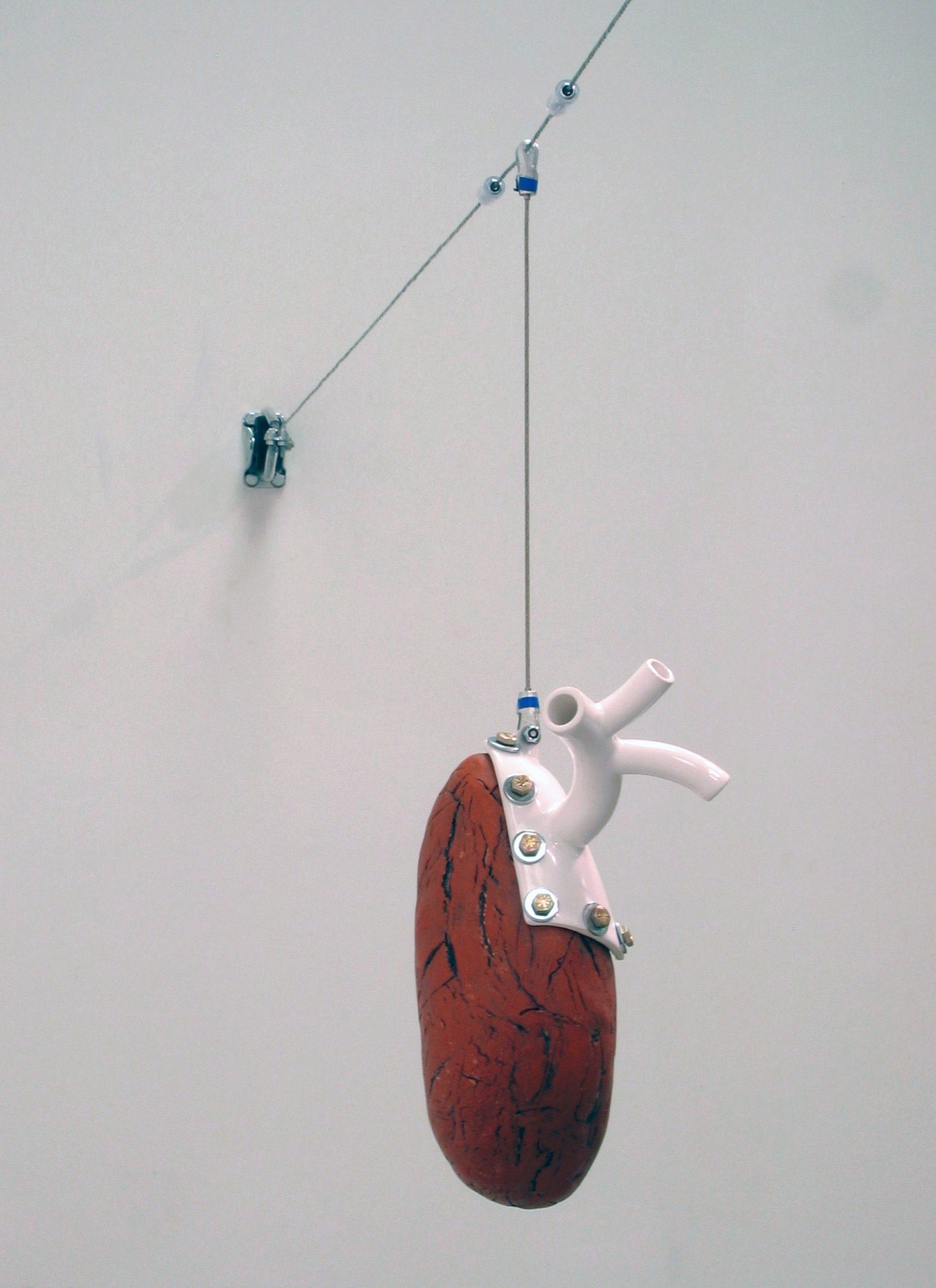

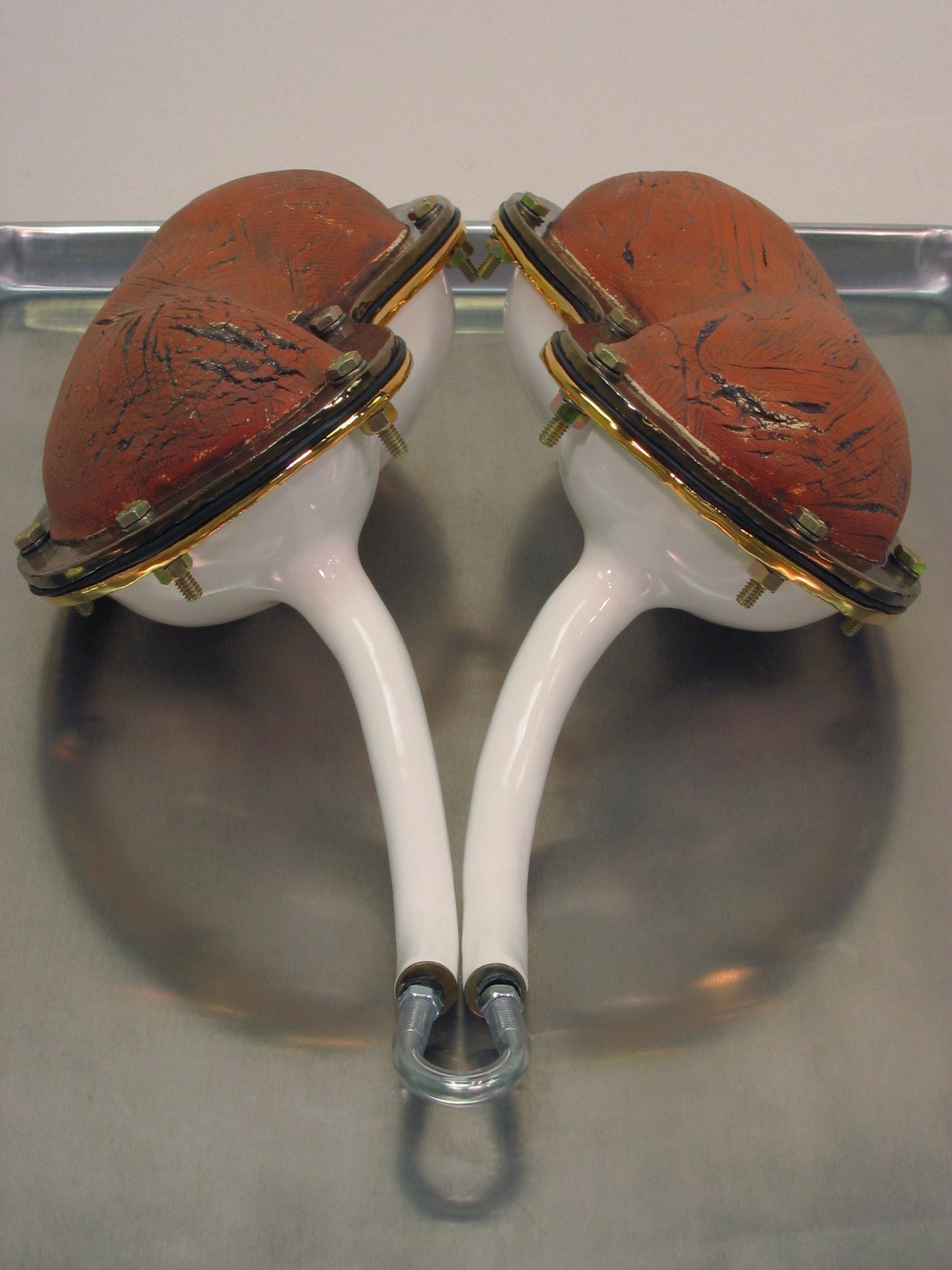

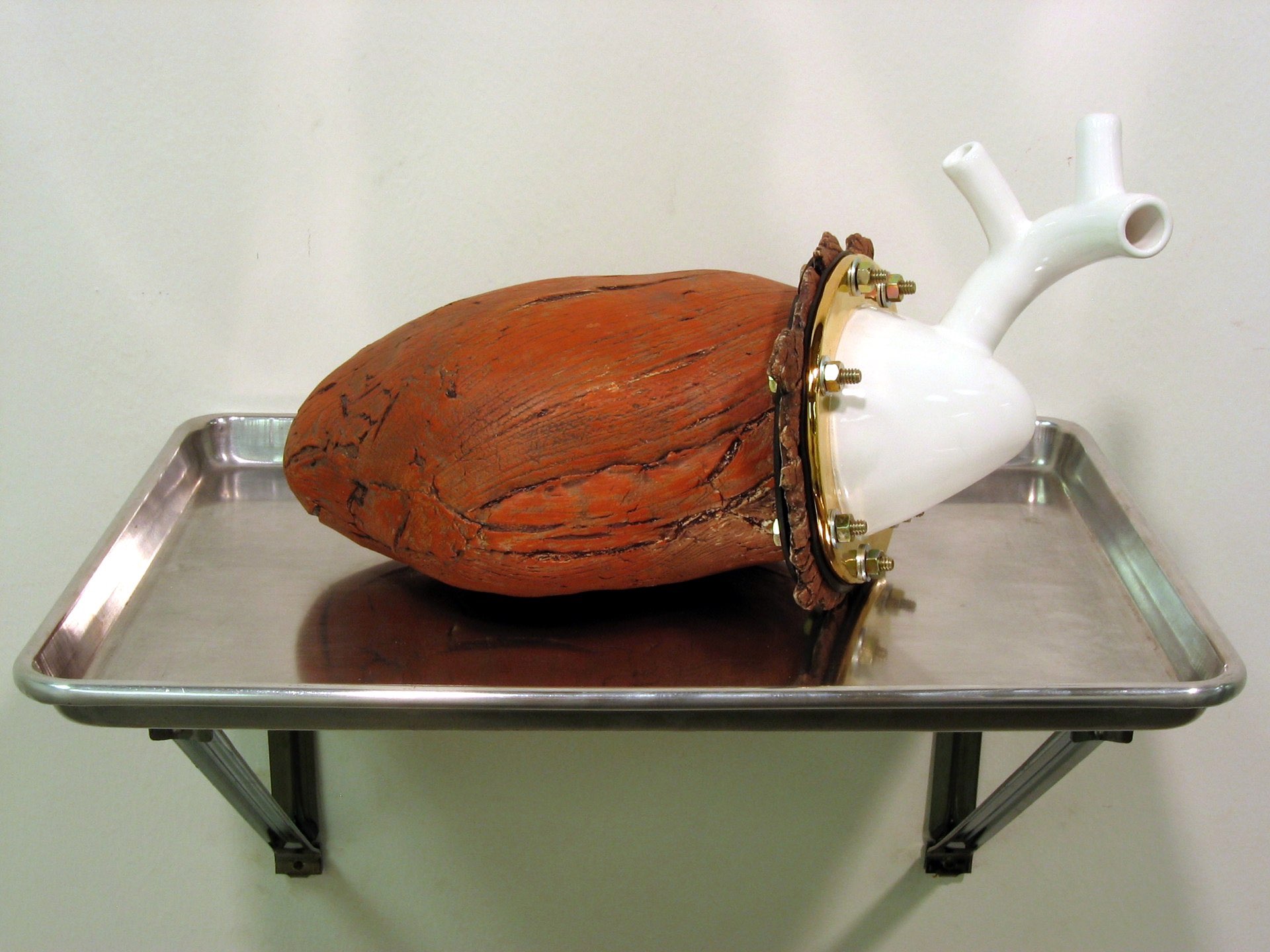

Imagined and fabricated objects developed from collective and personal histories of place and form.

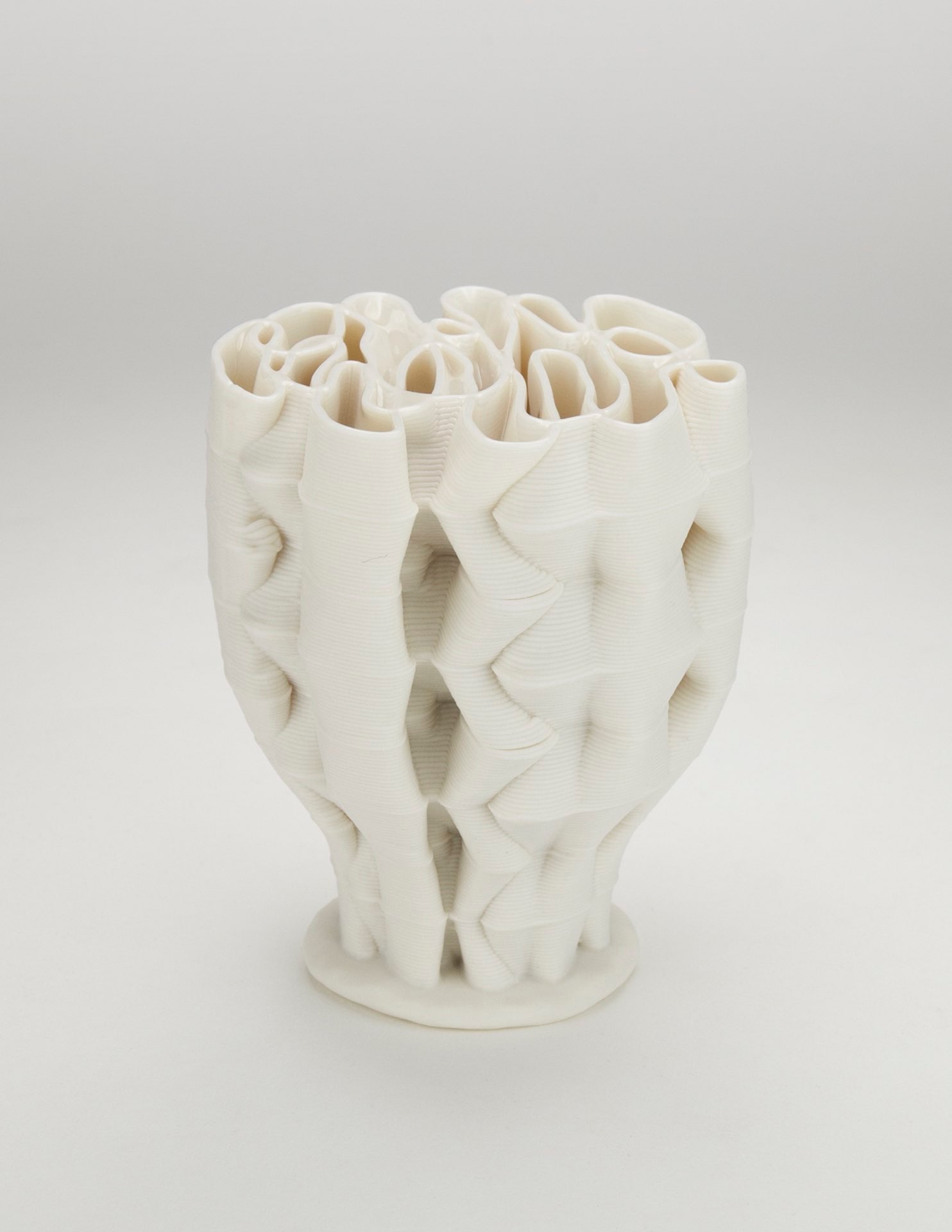

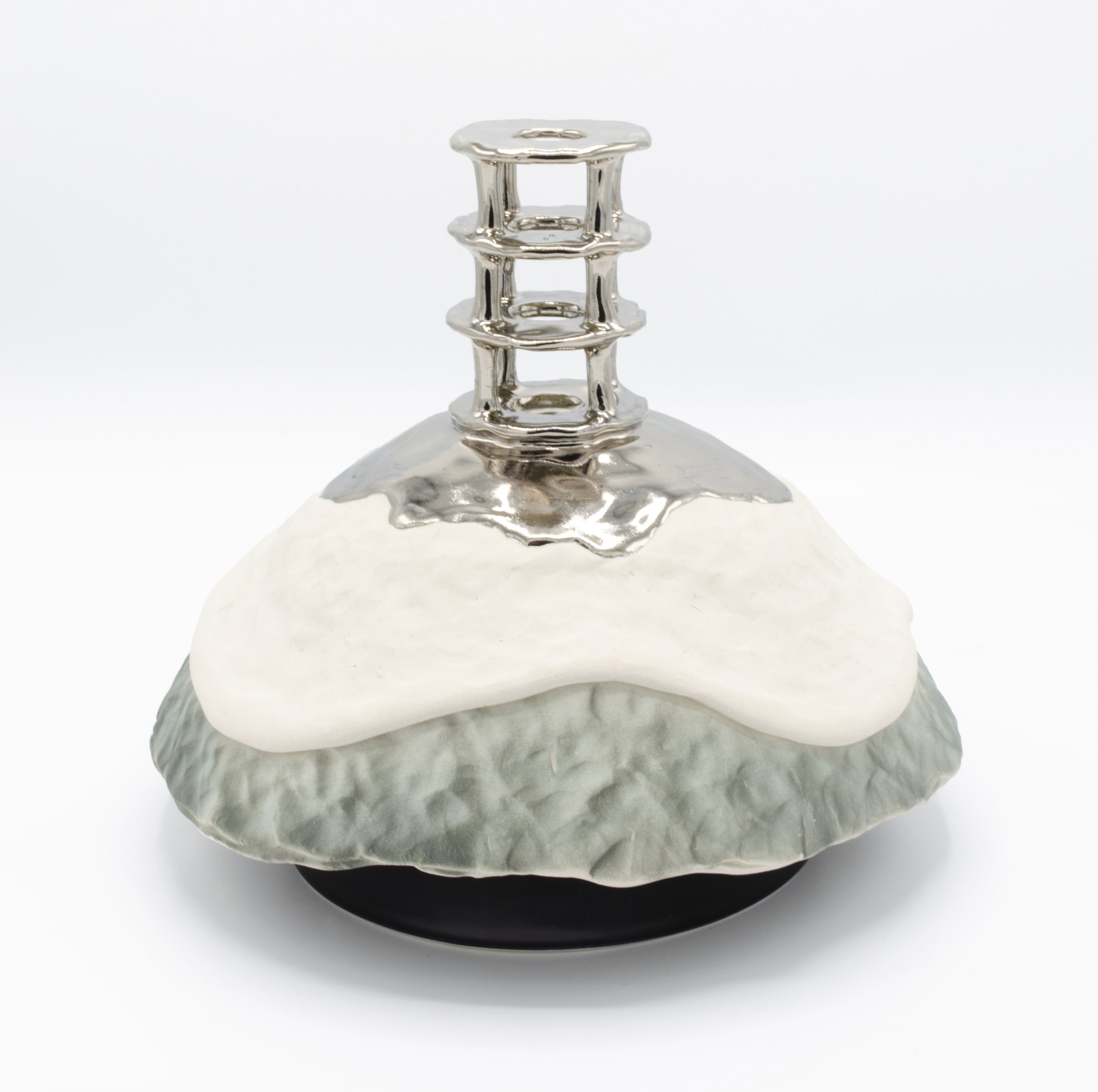

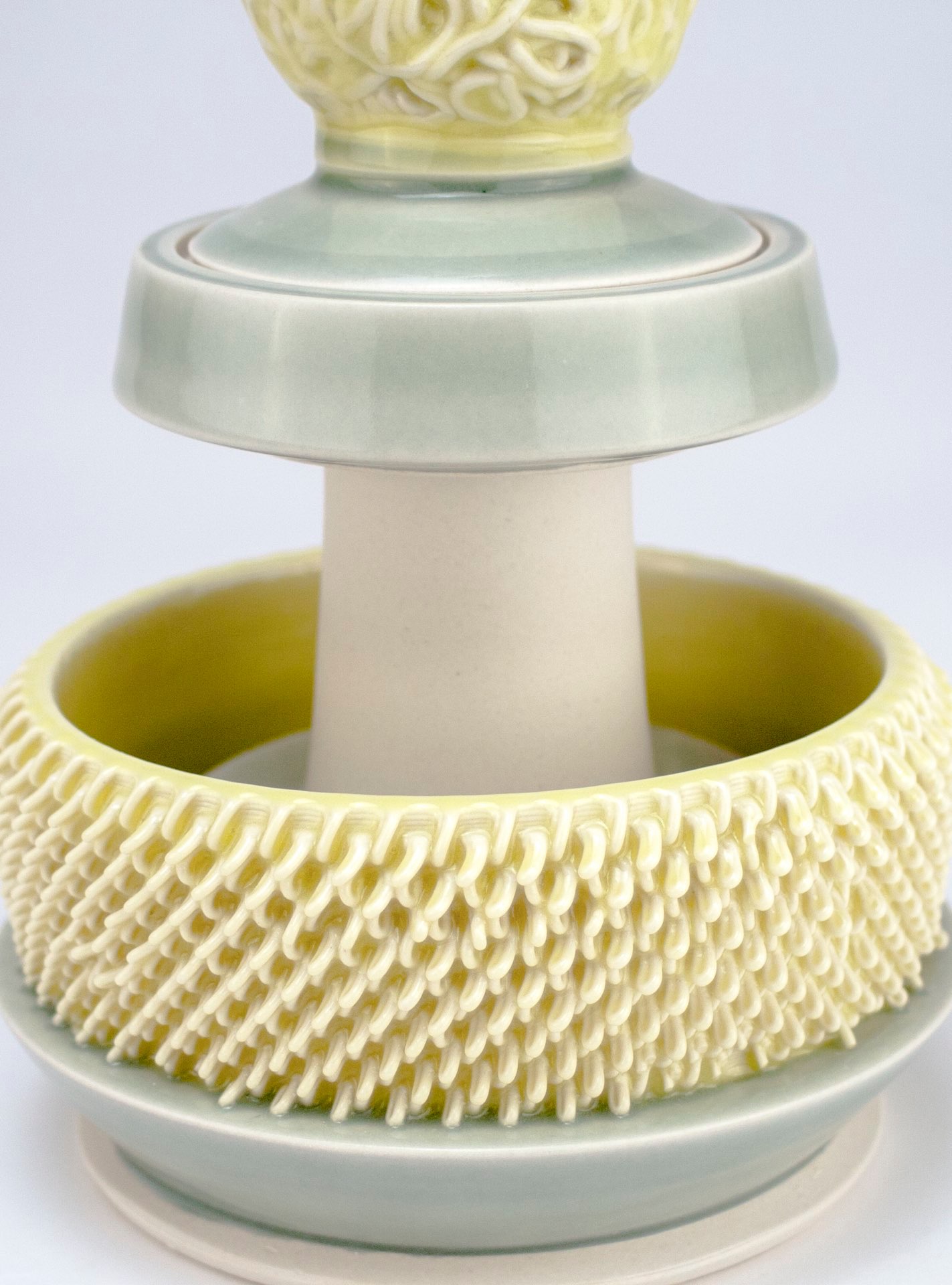

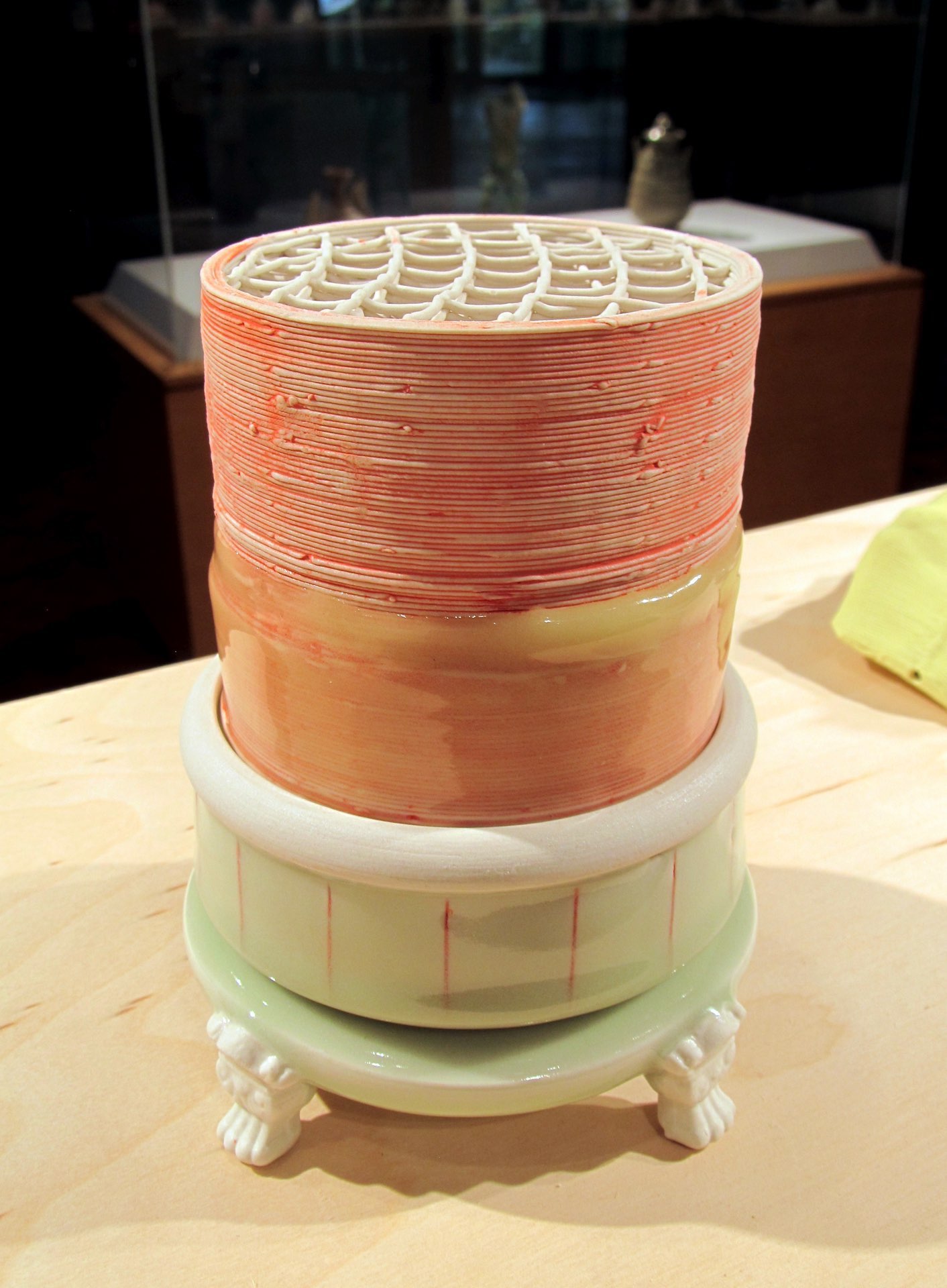

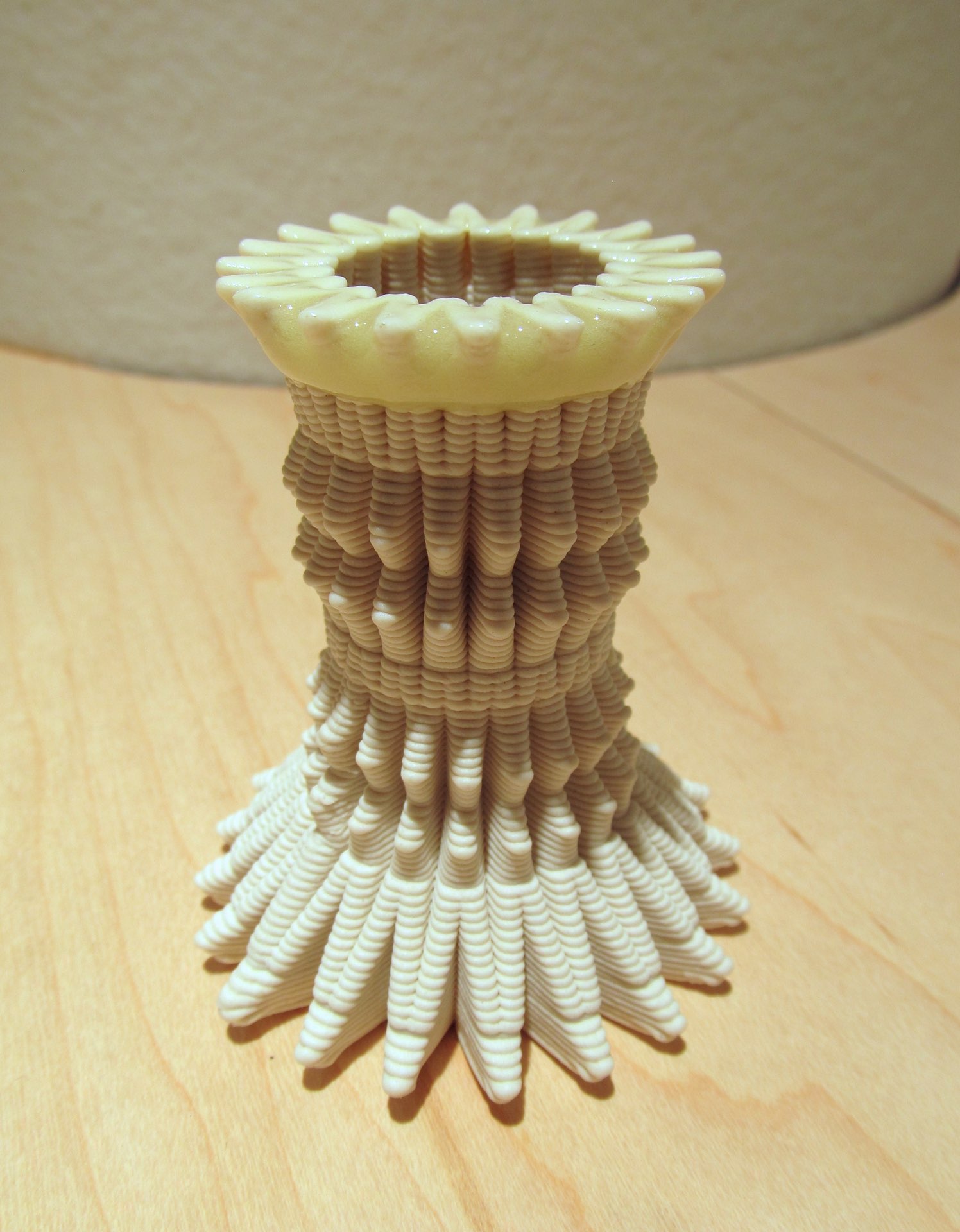

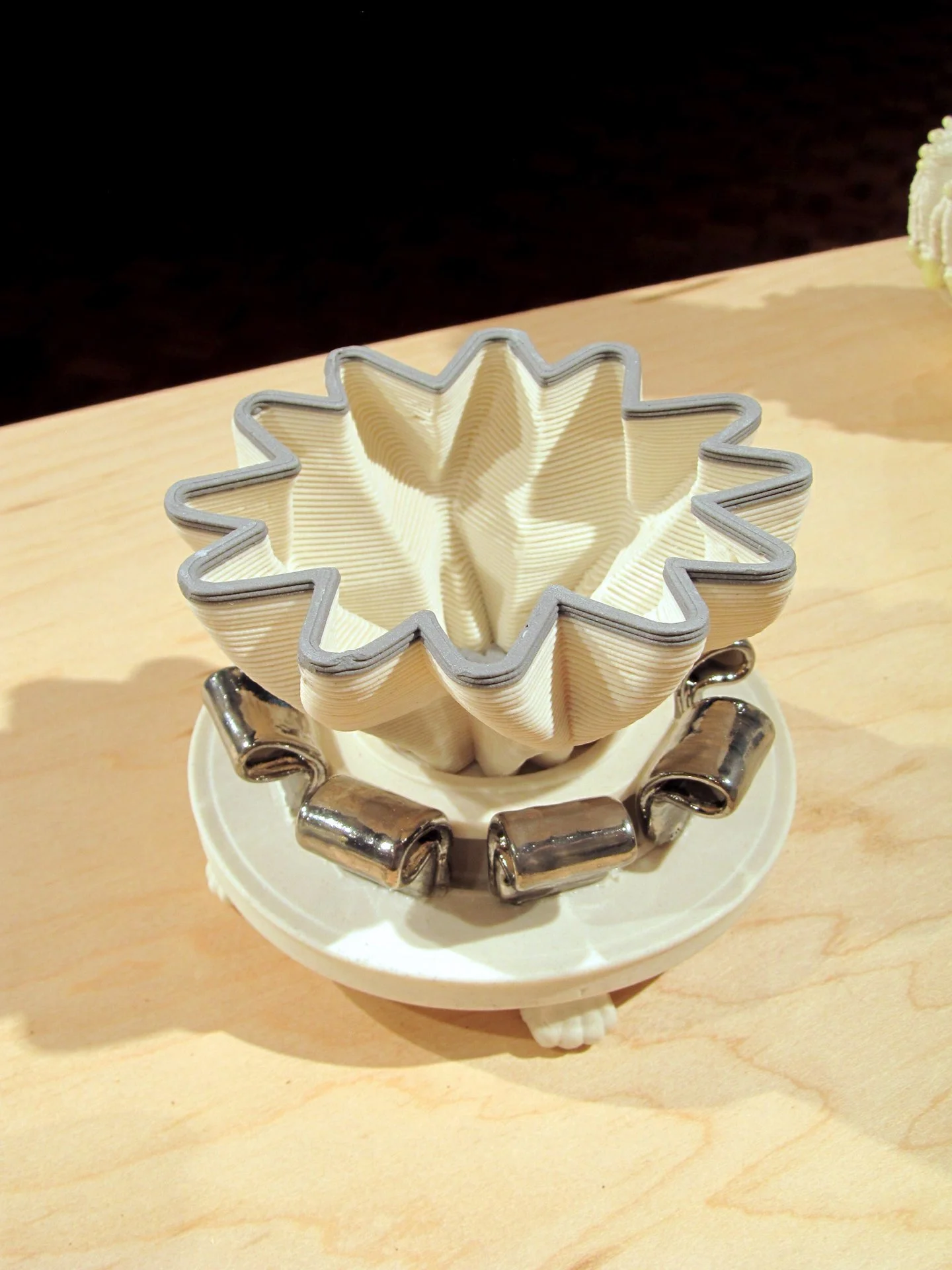

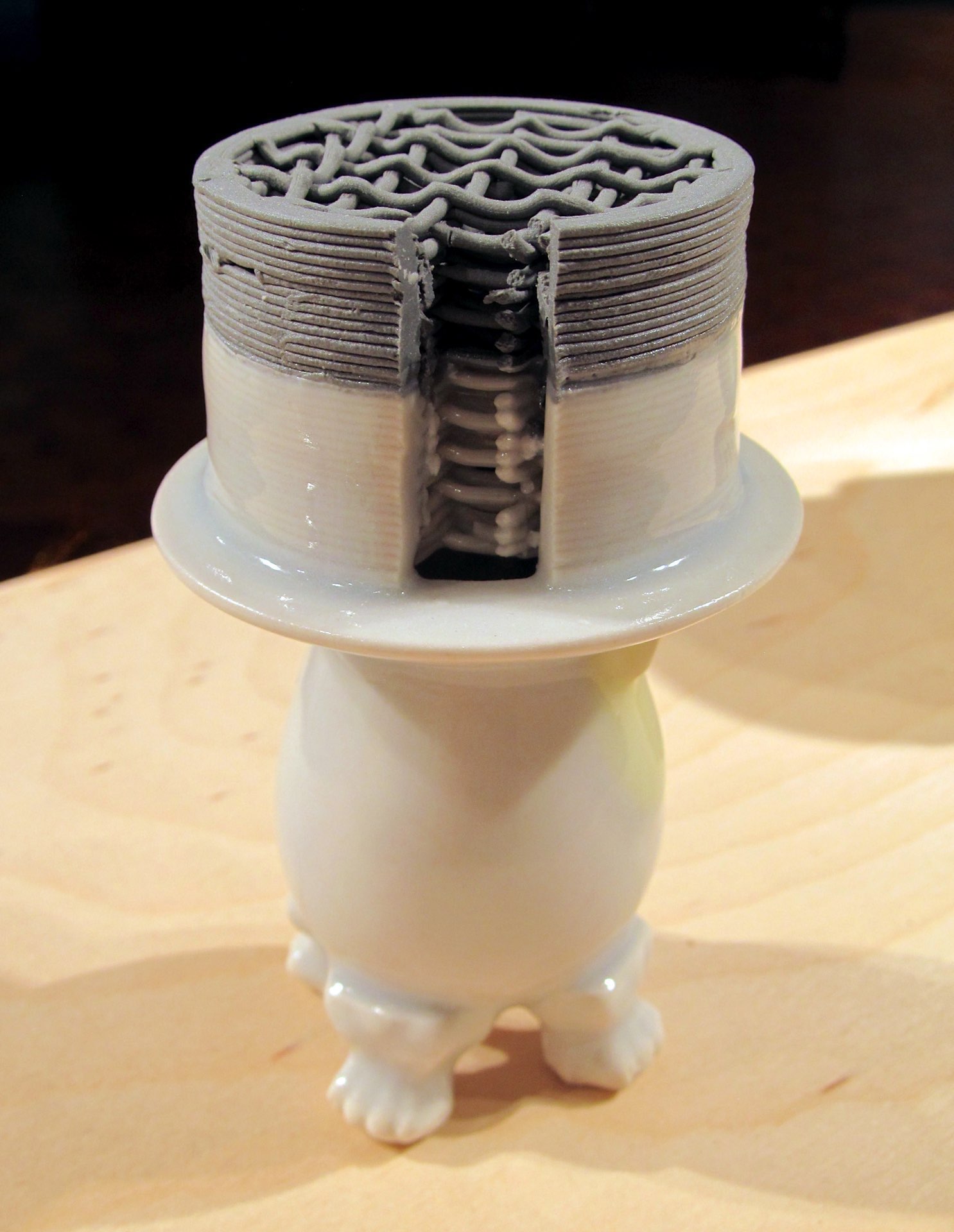

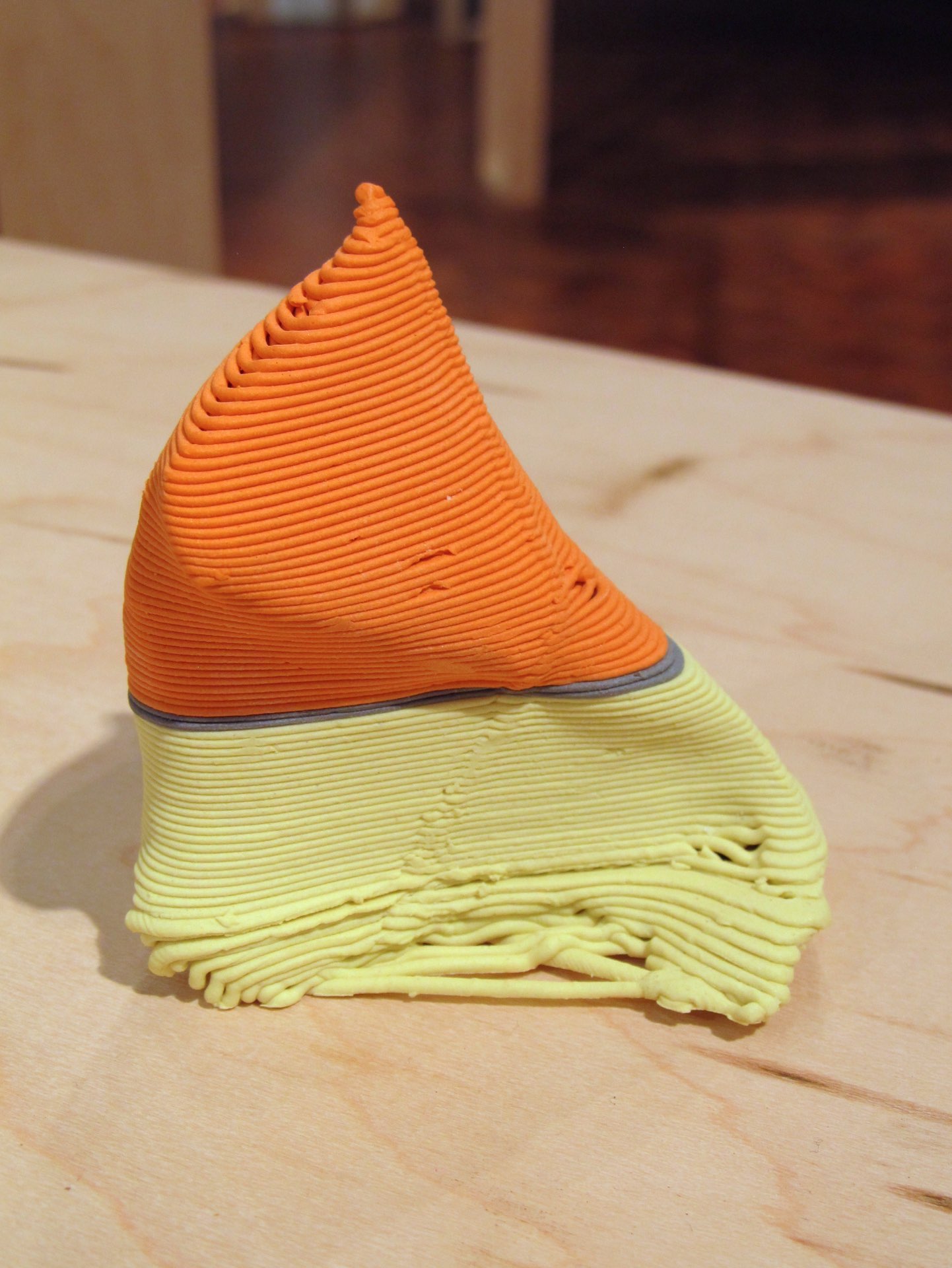

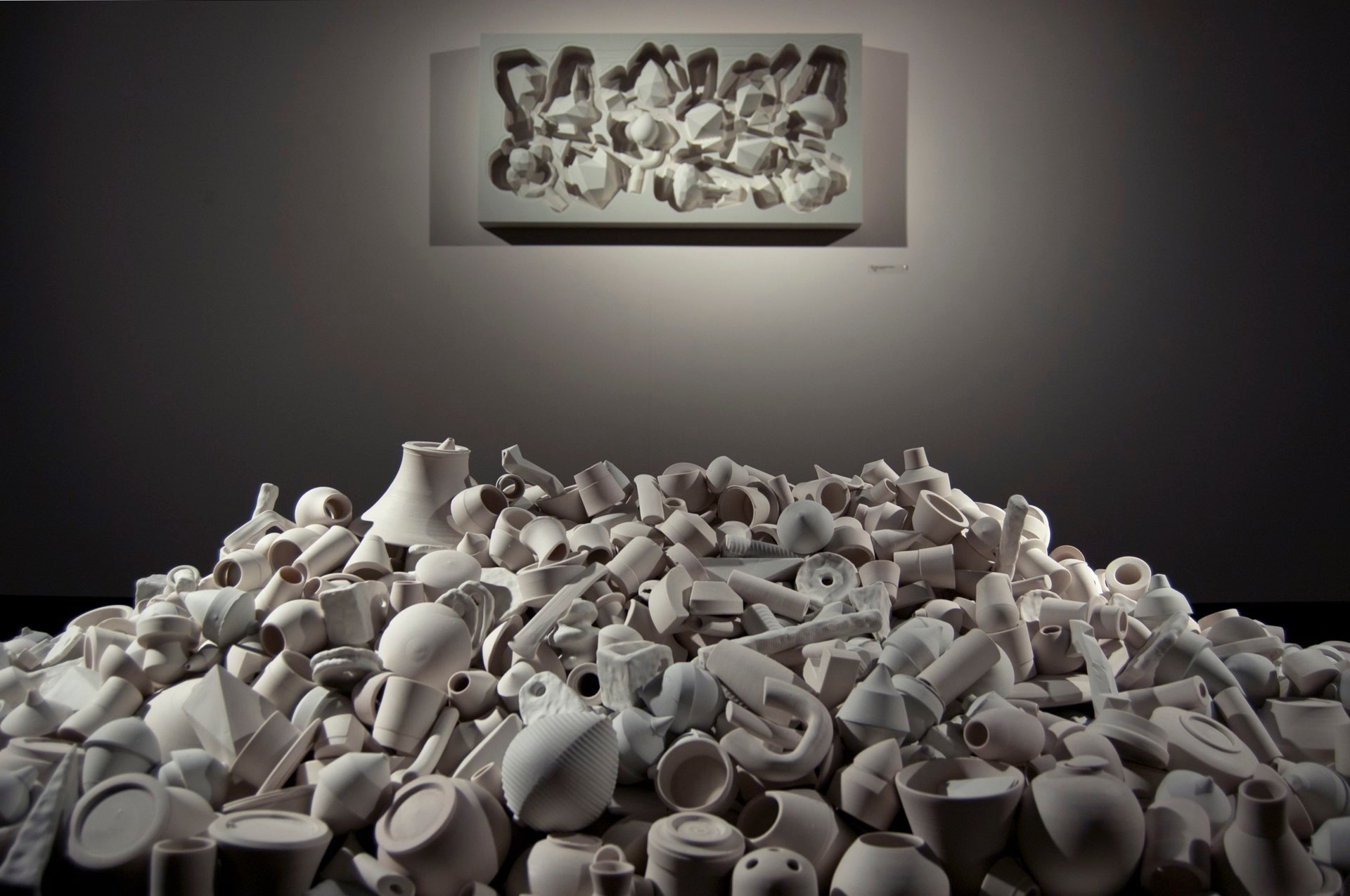

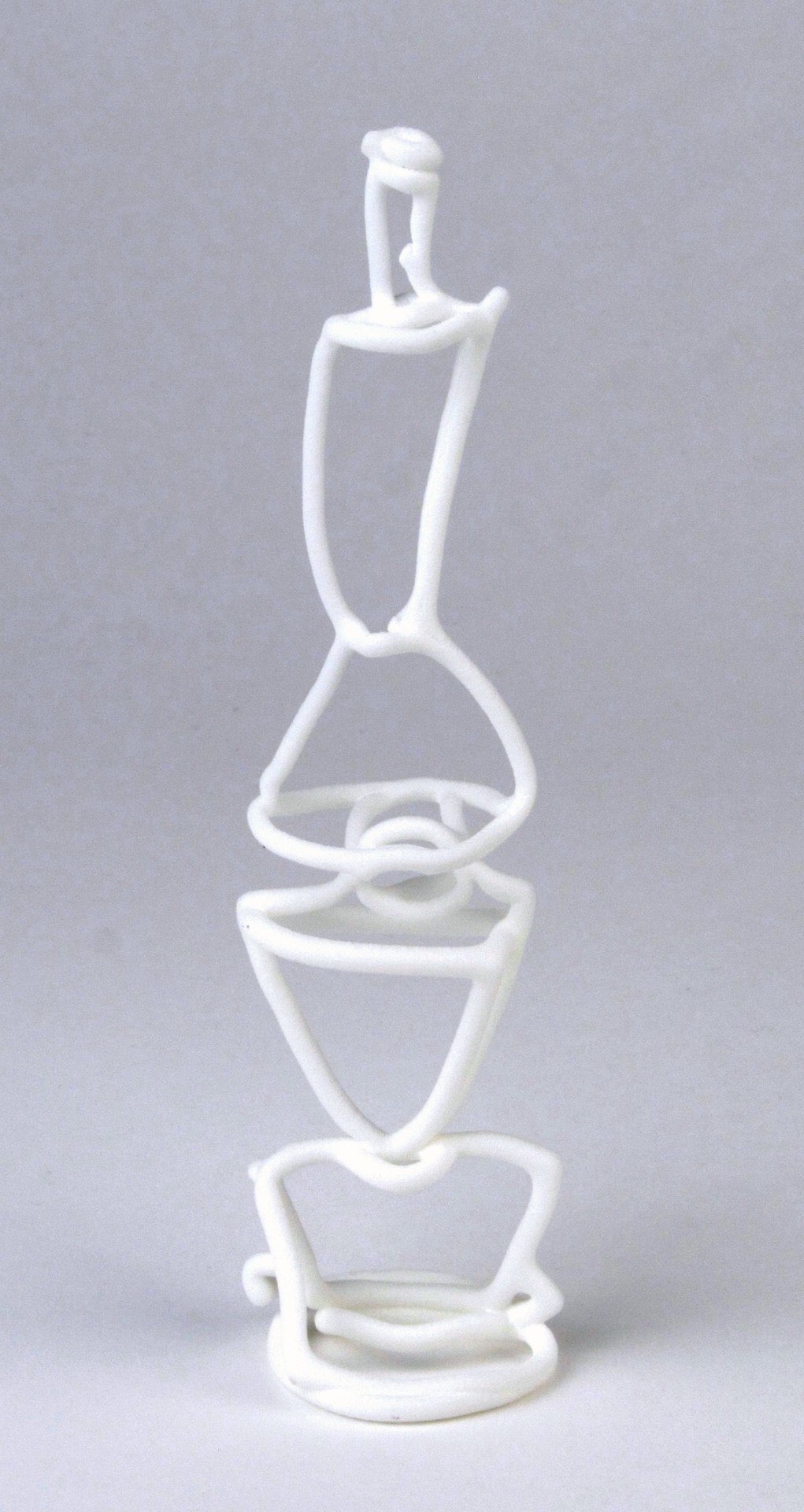

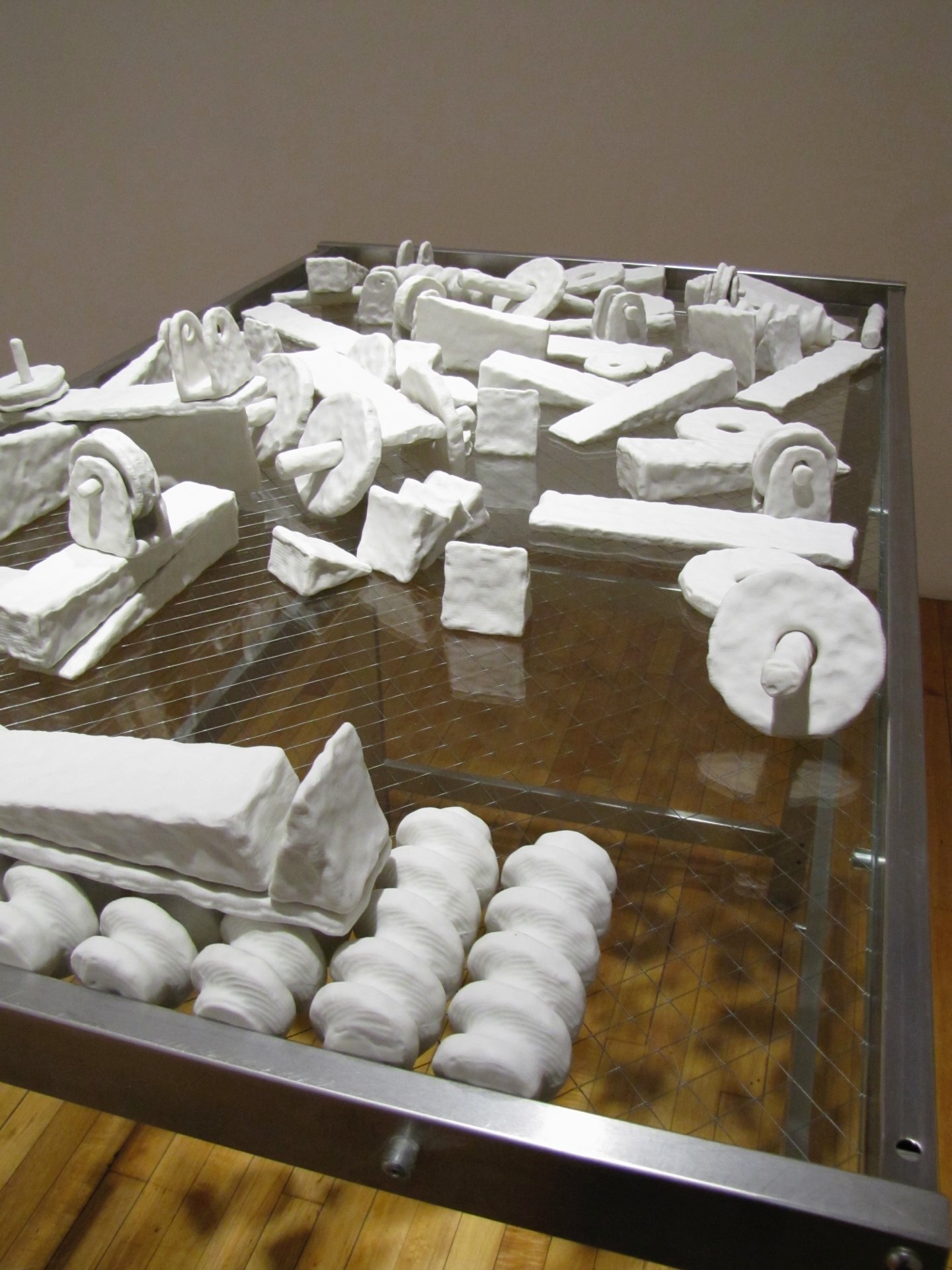

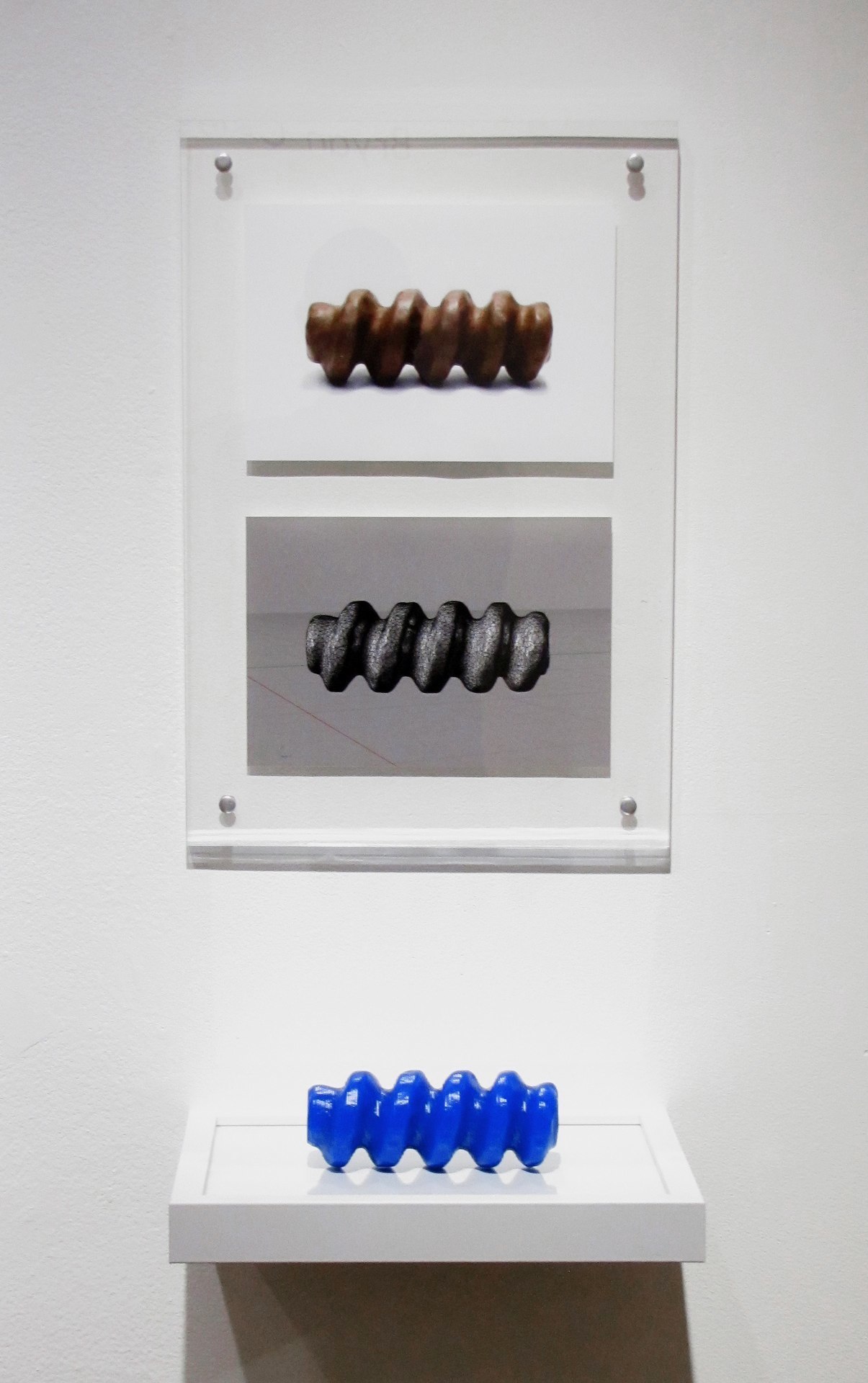

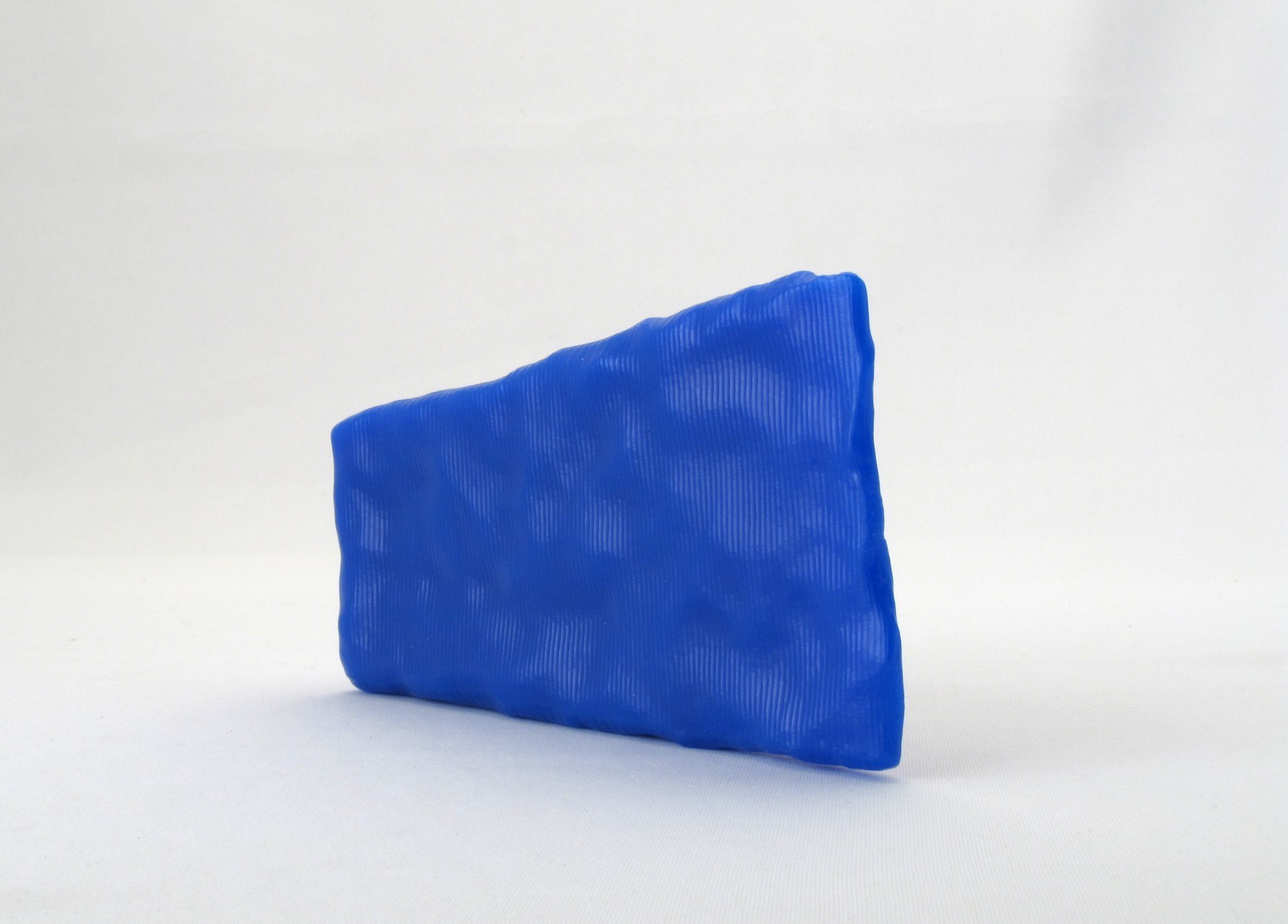

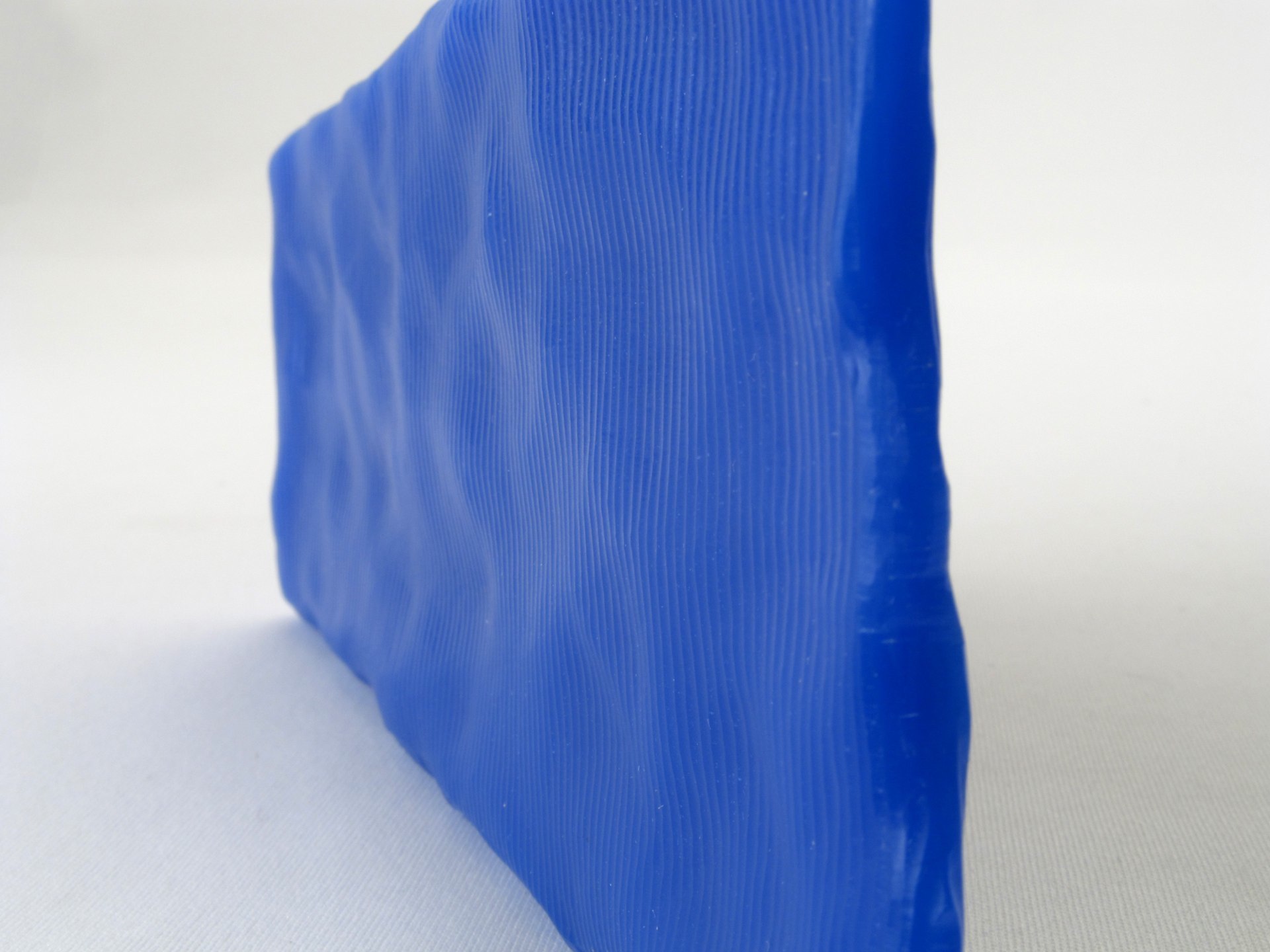

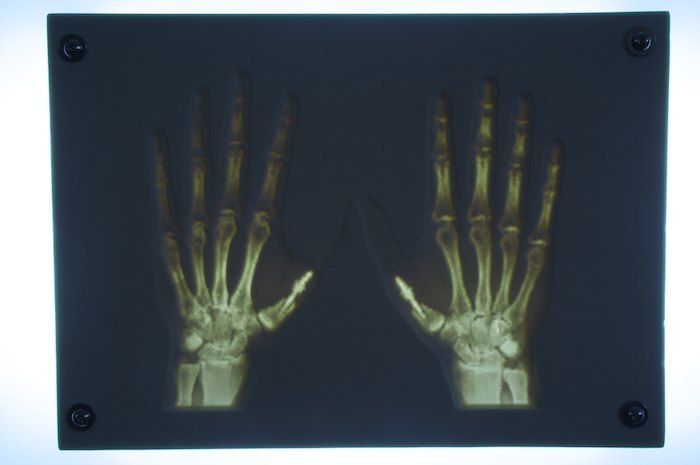

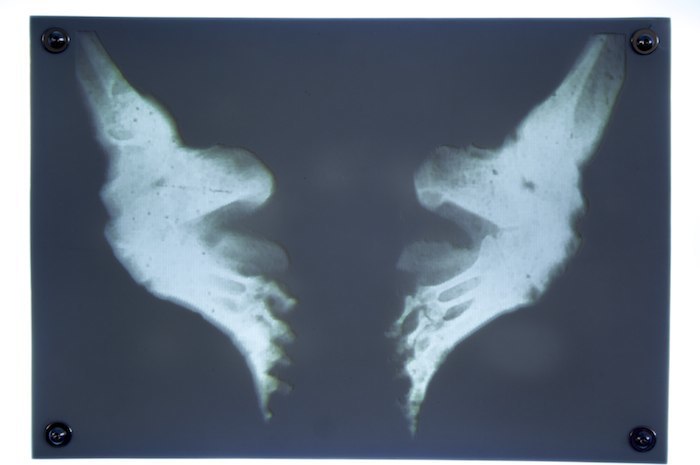

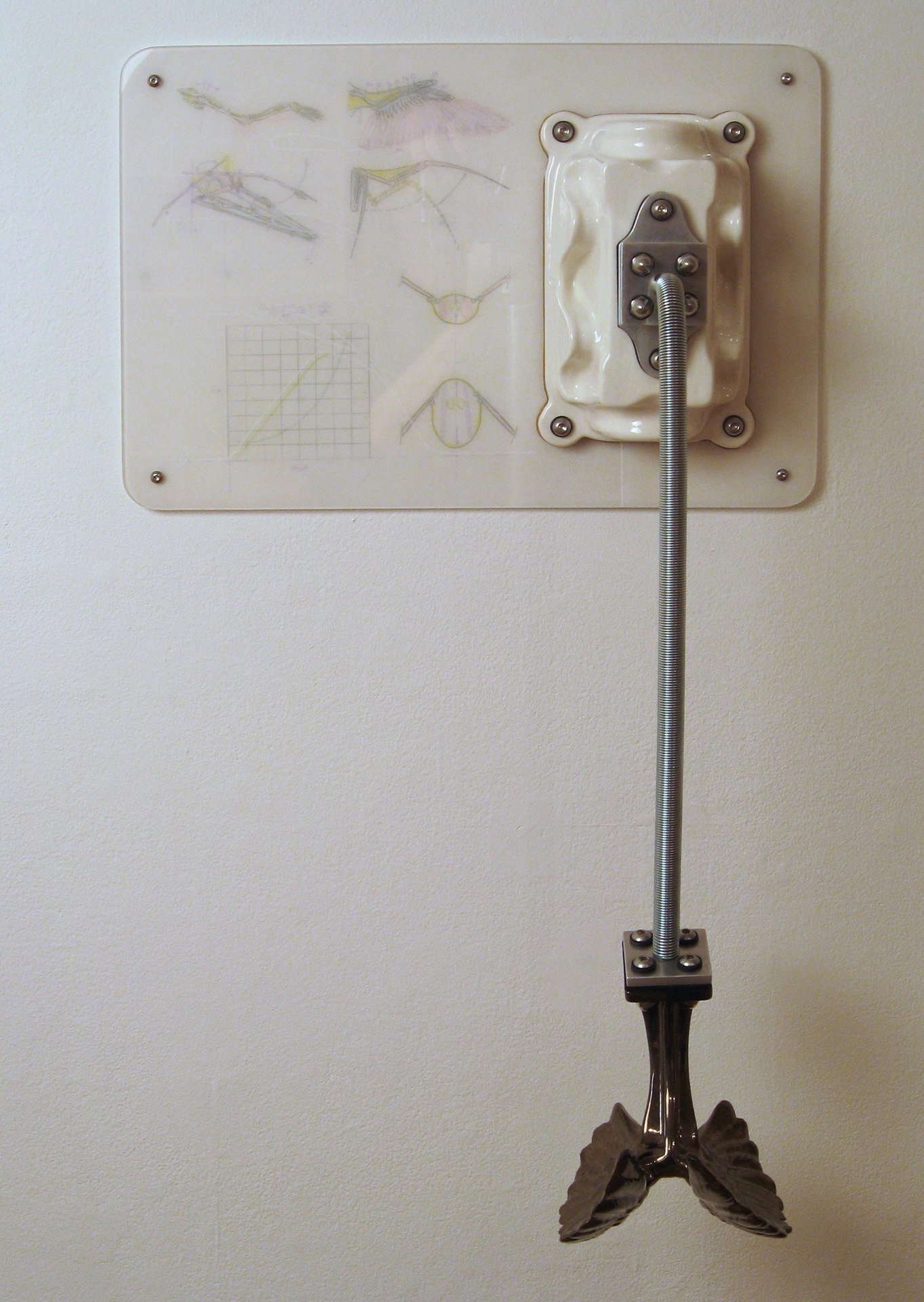

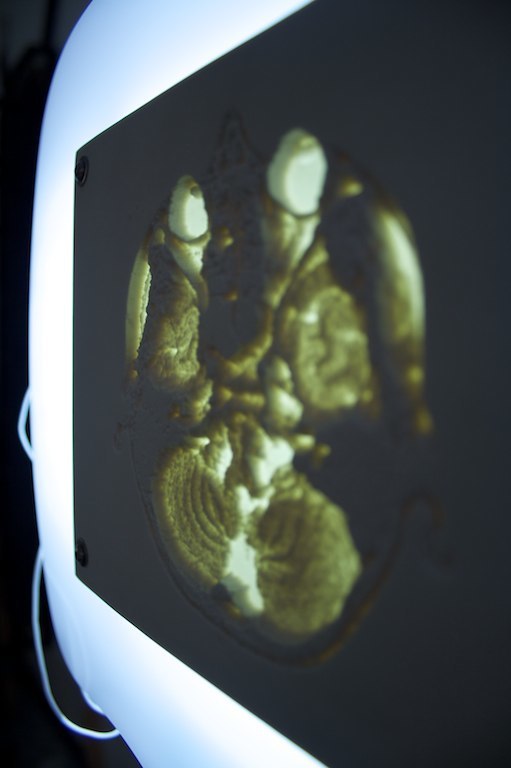

3d printed and hand built porcelain from photogrammetric digital scans in Budapest, Kiskunfelegyhaza, Rome, and Pompeii.

This work is ongoing.

From the 2019 Northern Clay Center McKnight Catalog:

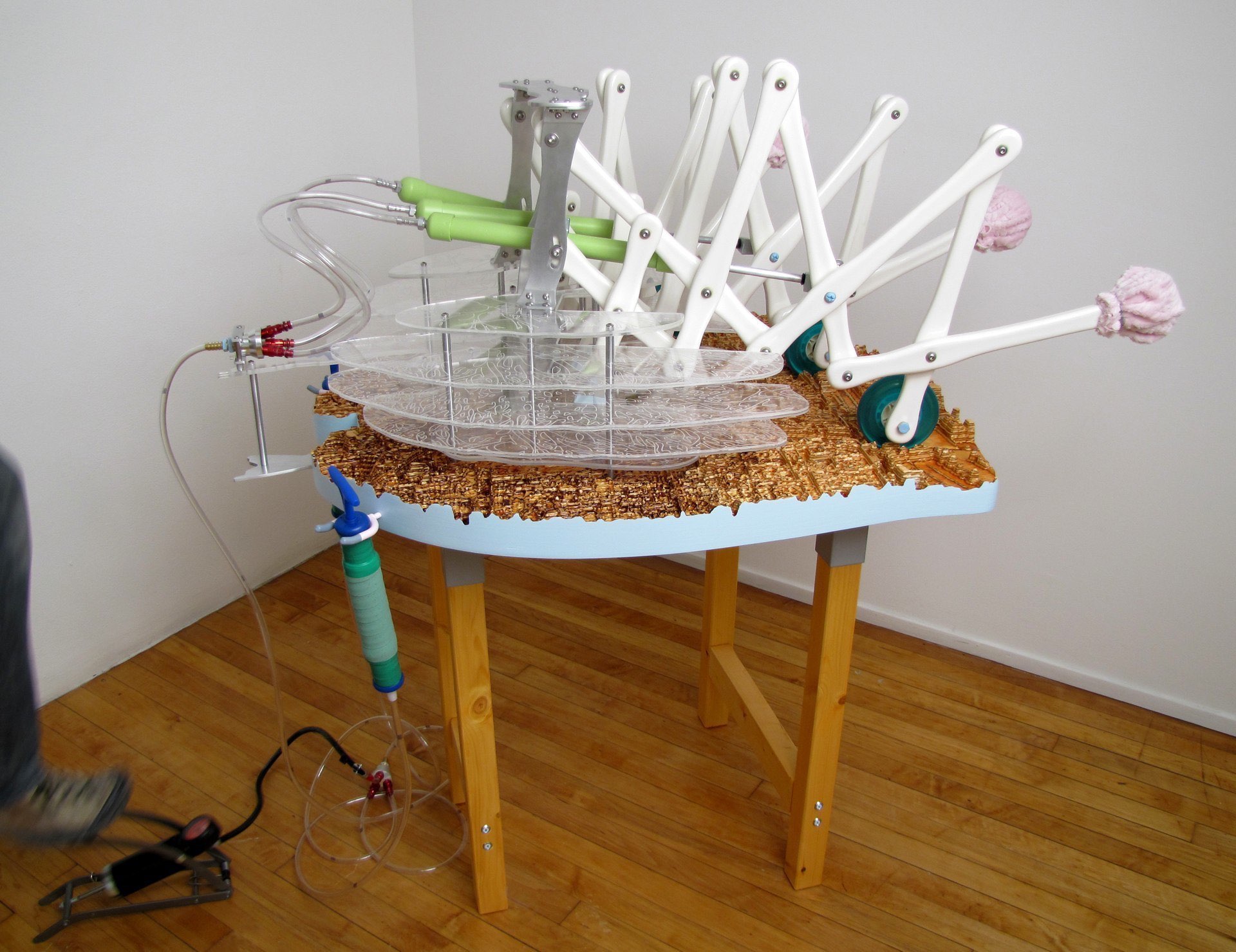

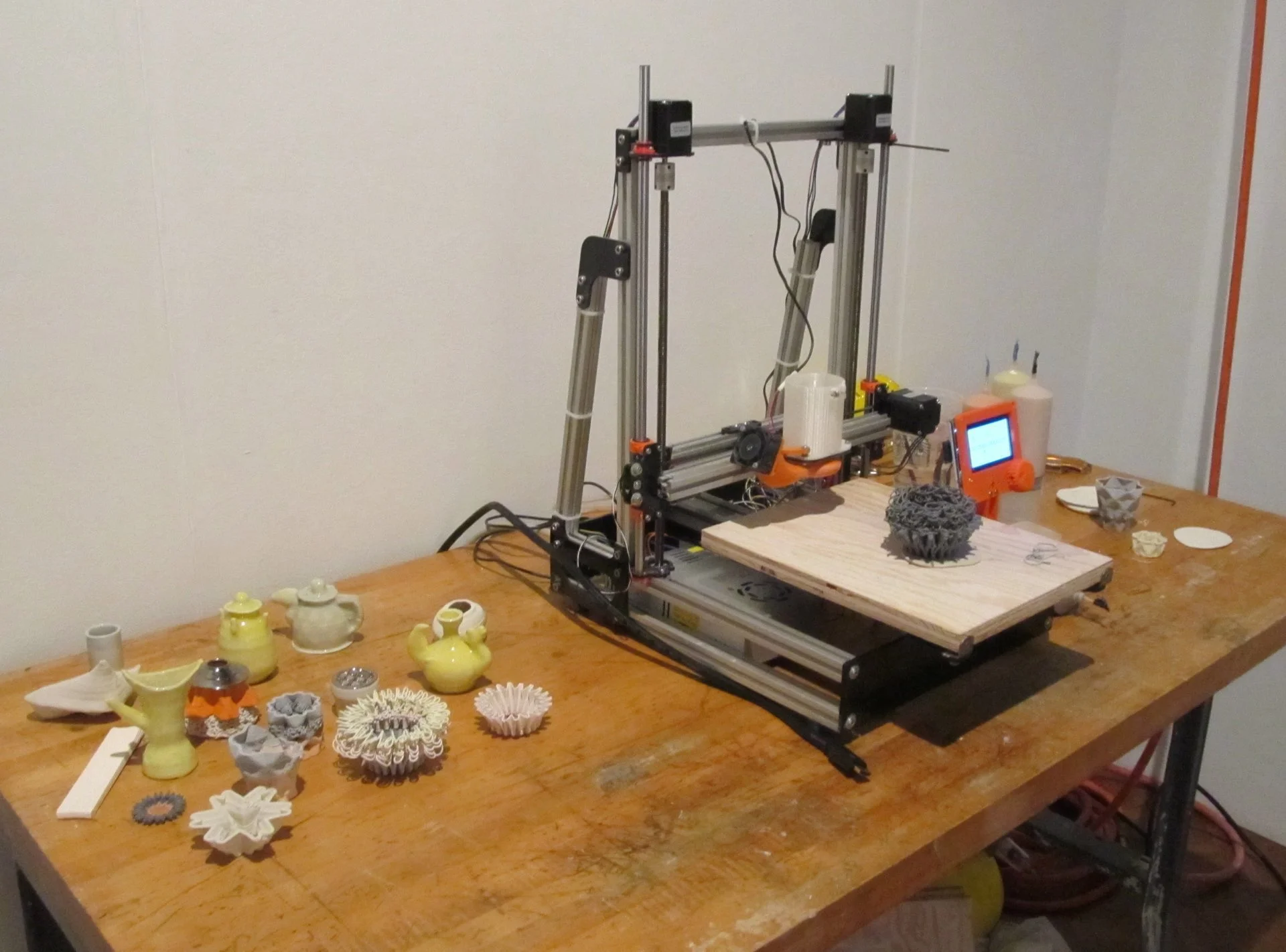

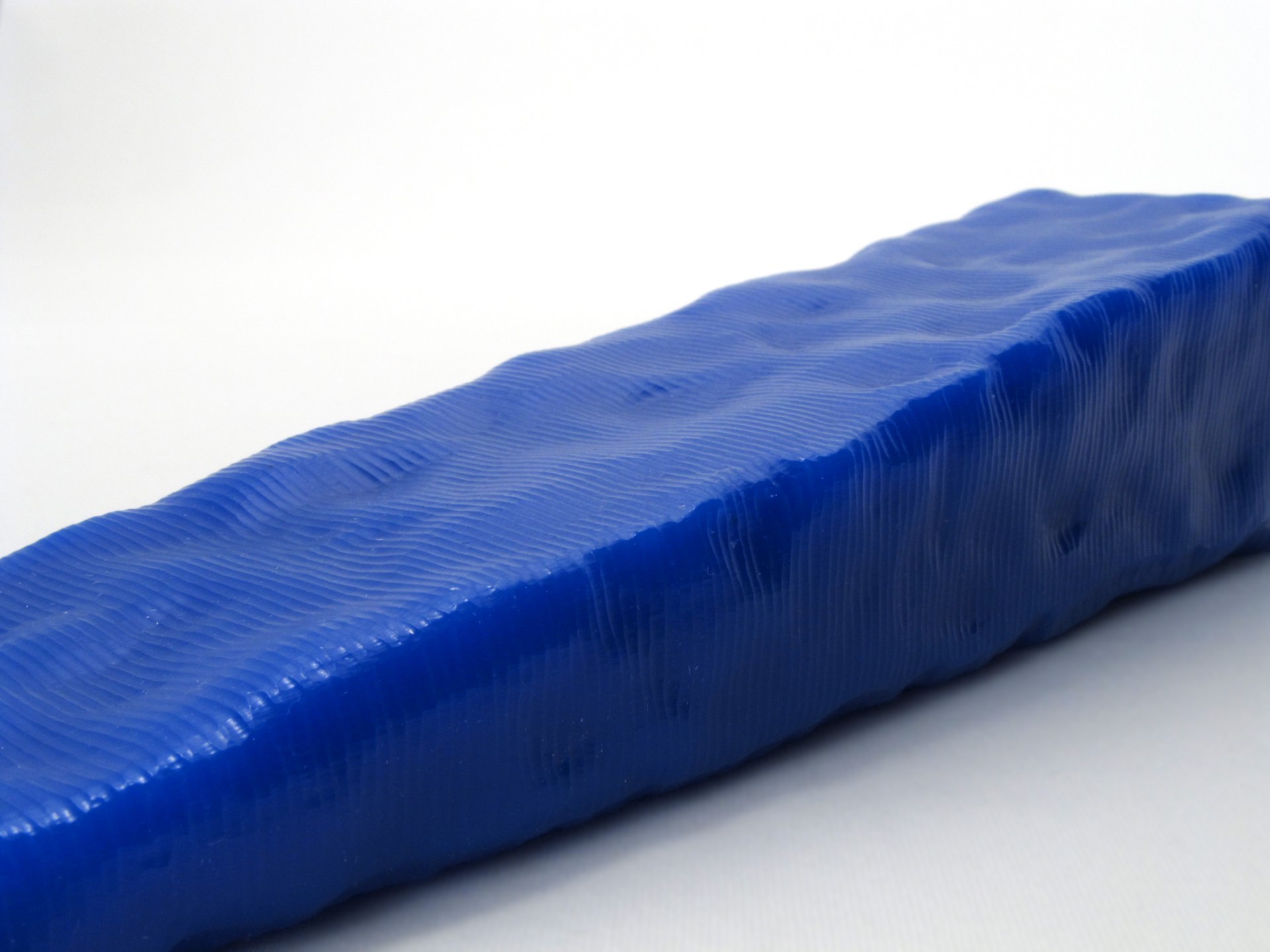

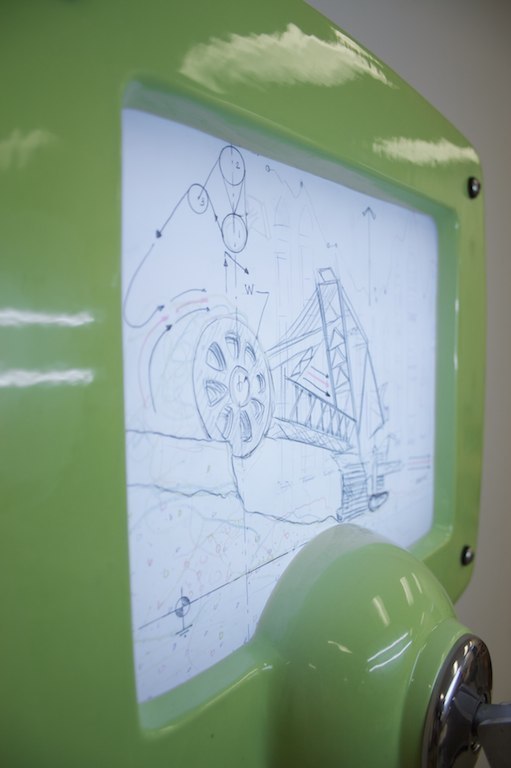

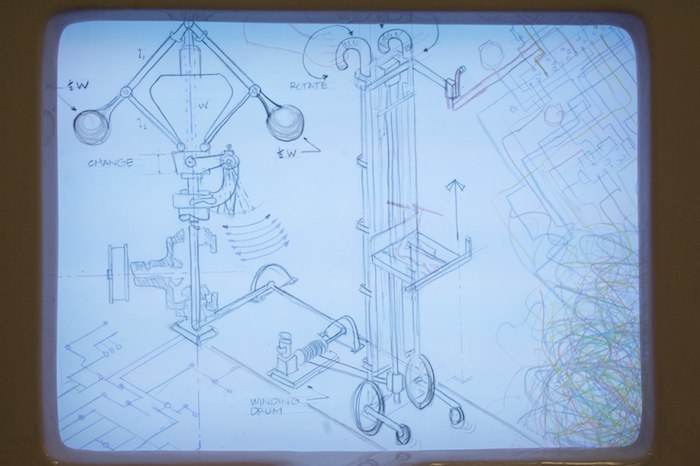

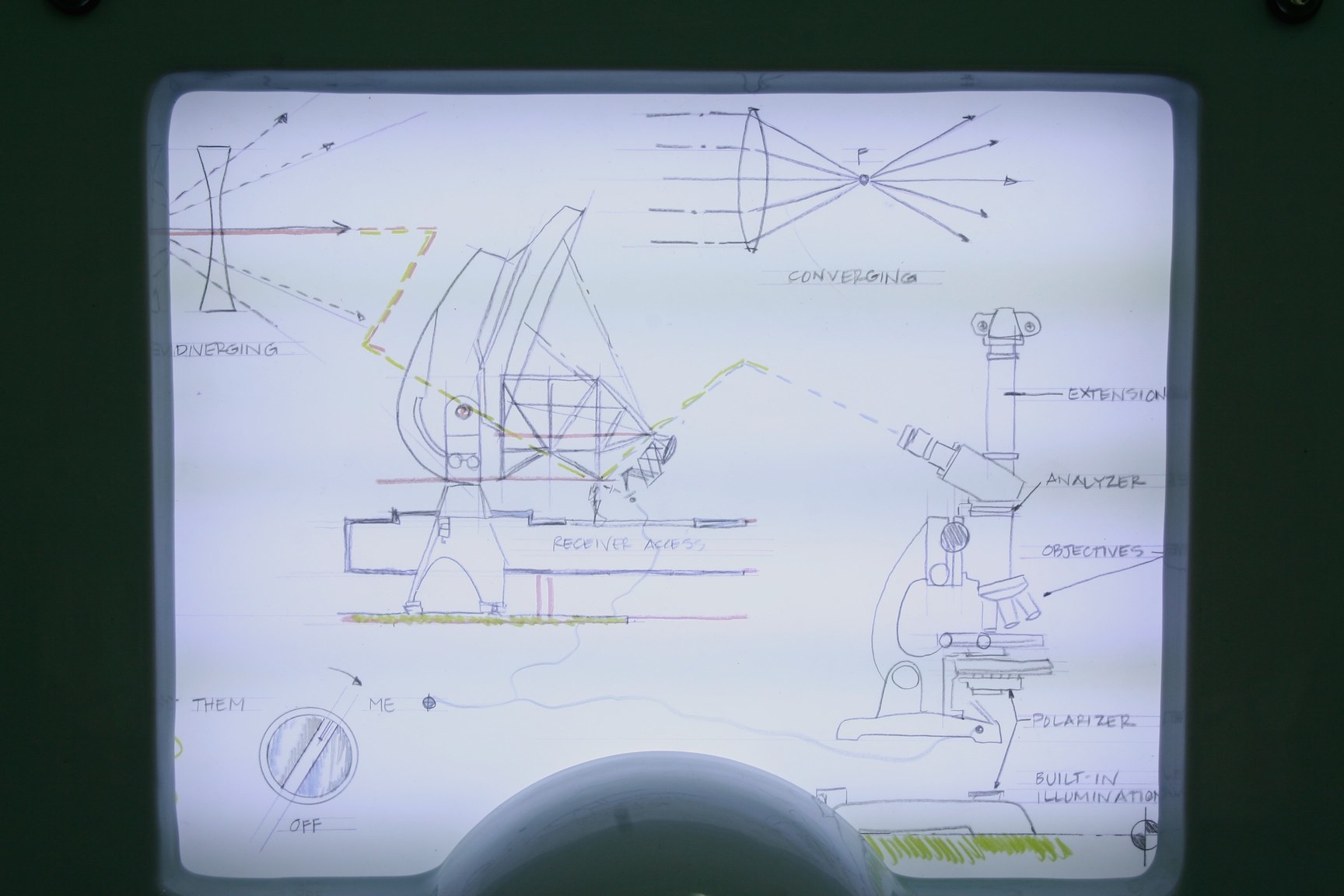

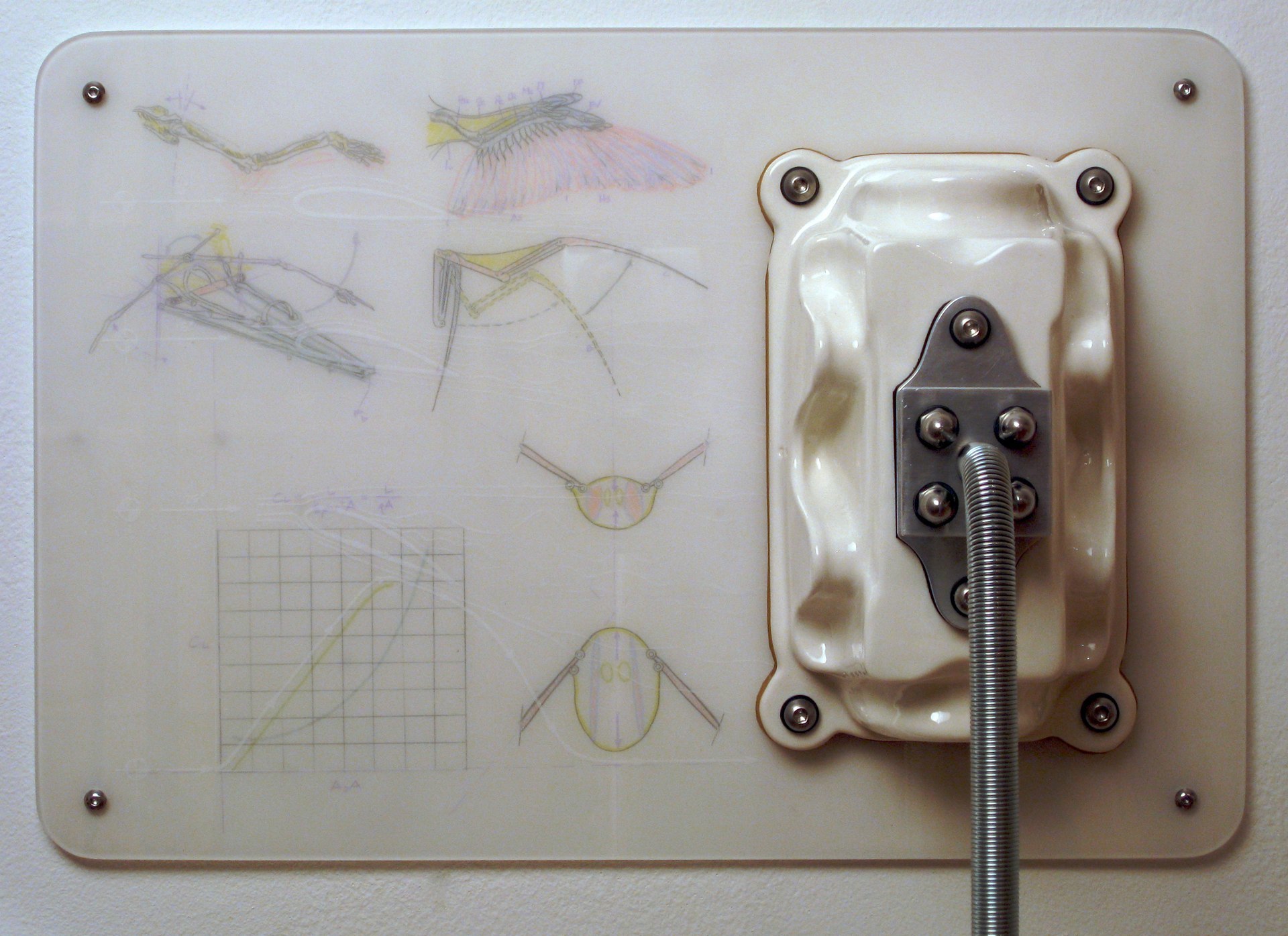

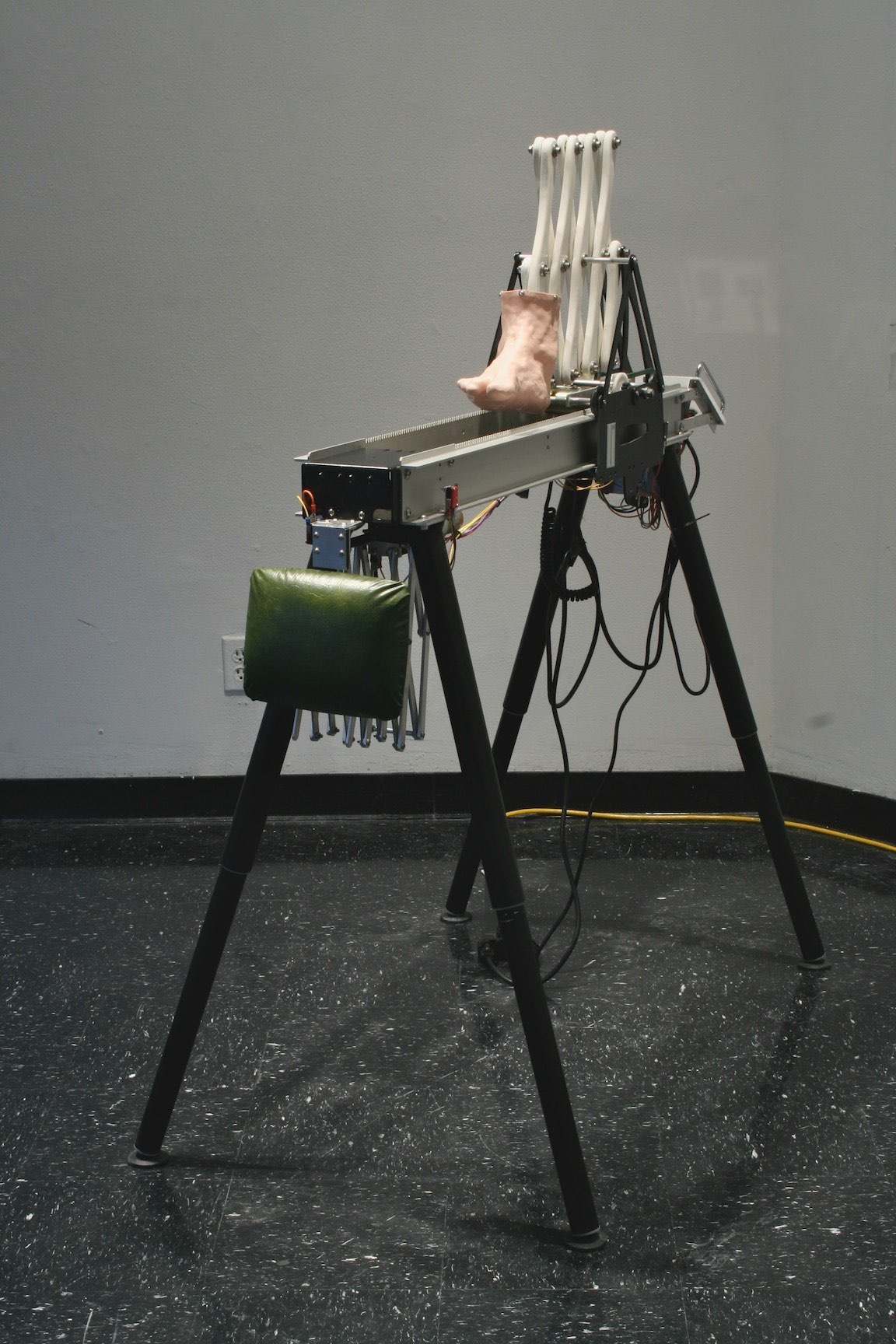

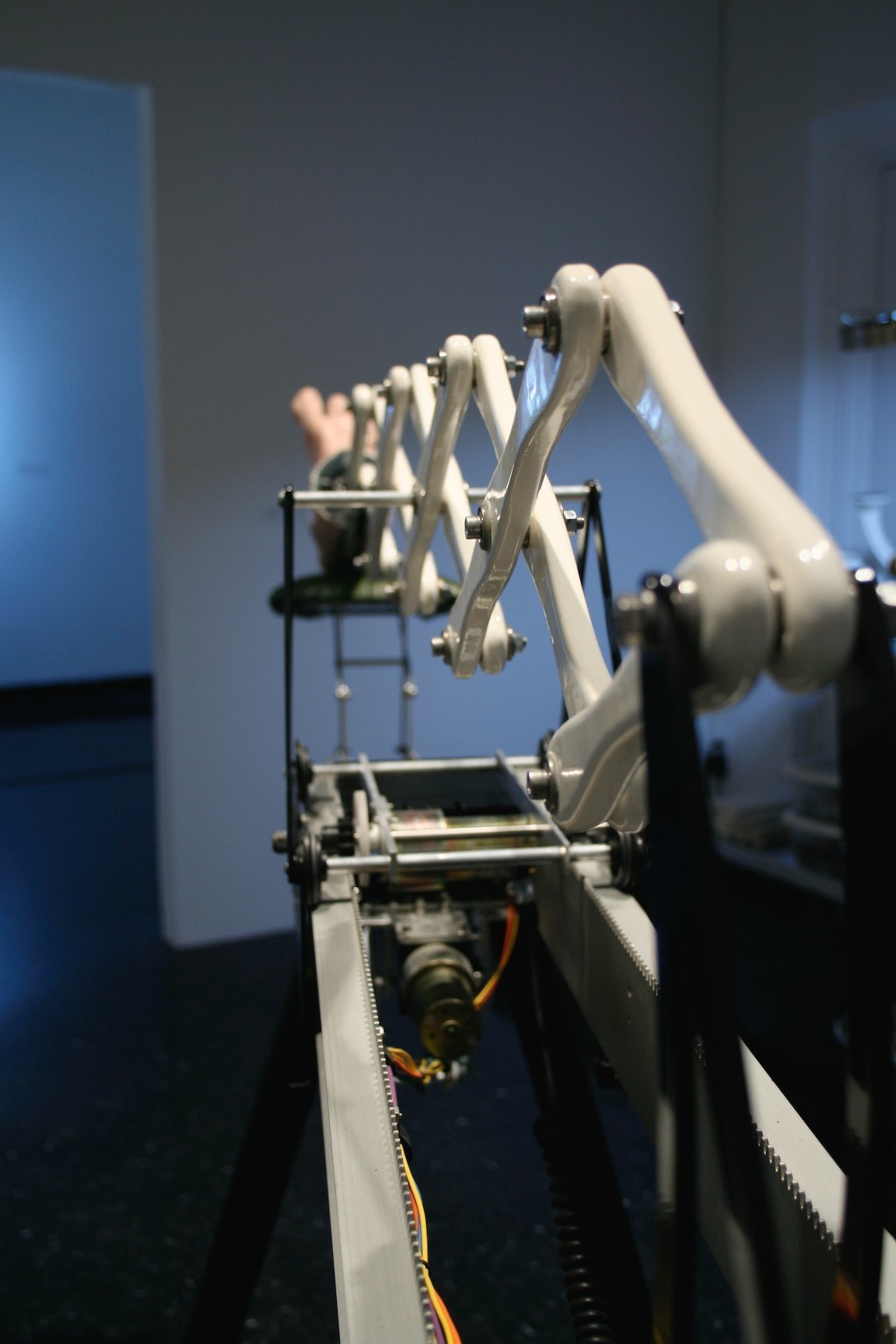

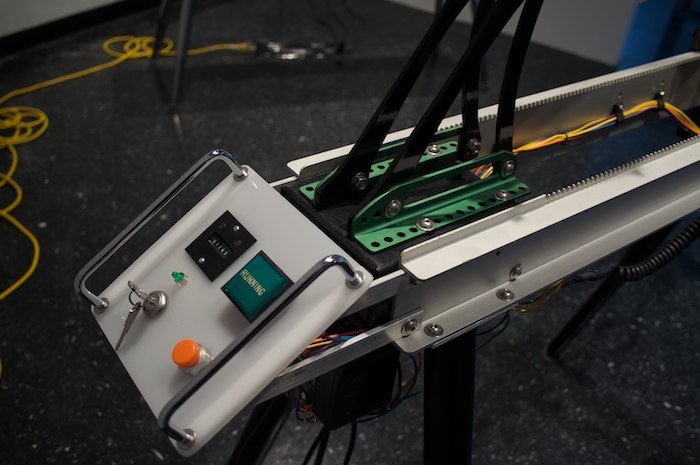

“While much of ceramic tradition remains unchanged, it’s unlikely that a potter from 100 years ago would recognize the tools of their trade in Bryan Czibesz’s practice. Czibesz’s groundbreaking work was among the first in ceramics to utilize rapid prototyping (3D printing) technology in ways that expanded the field’s understanding of this new tool. Having built ceramic printers and then, having taught others to build and use these complex machine, Czibesz takes his mastery of this tool to the next level, intentionally disrupting and altering his work on multiple levels; in the algorithms and software, in the physically altered printing patterns, and in the manipulation of the printed object. Bryan’s interrogation of both objects and the means of their production suggest a kind of re-making in which objects become subject to new visualization, interpretation, and potential futures.

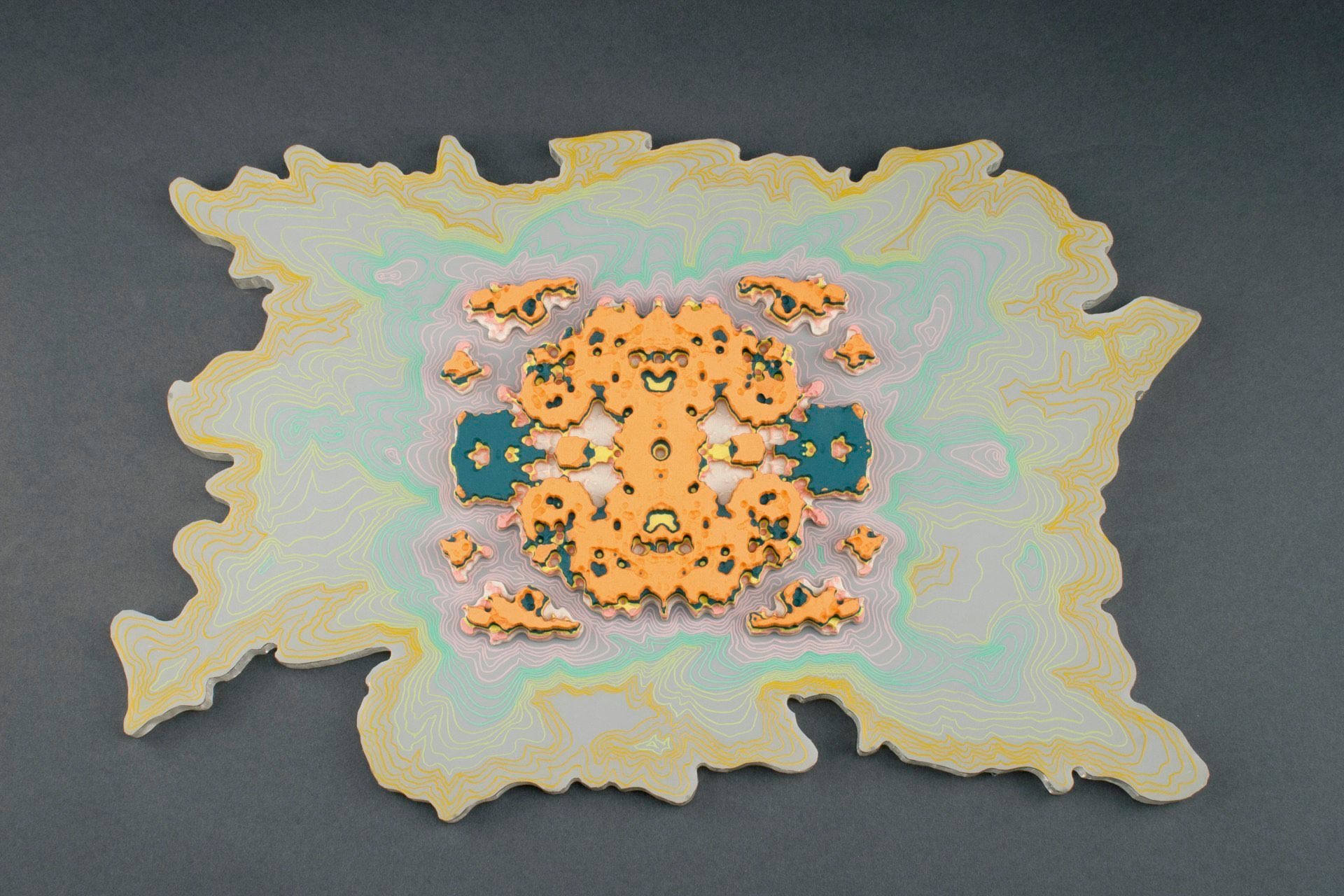

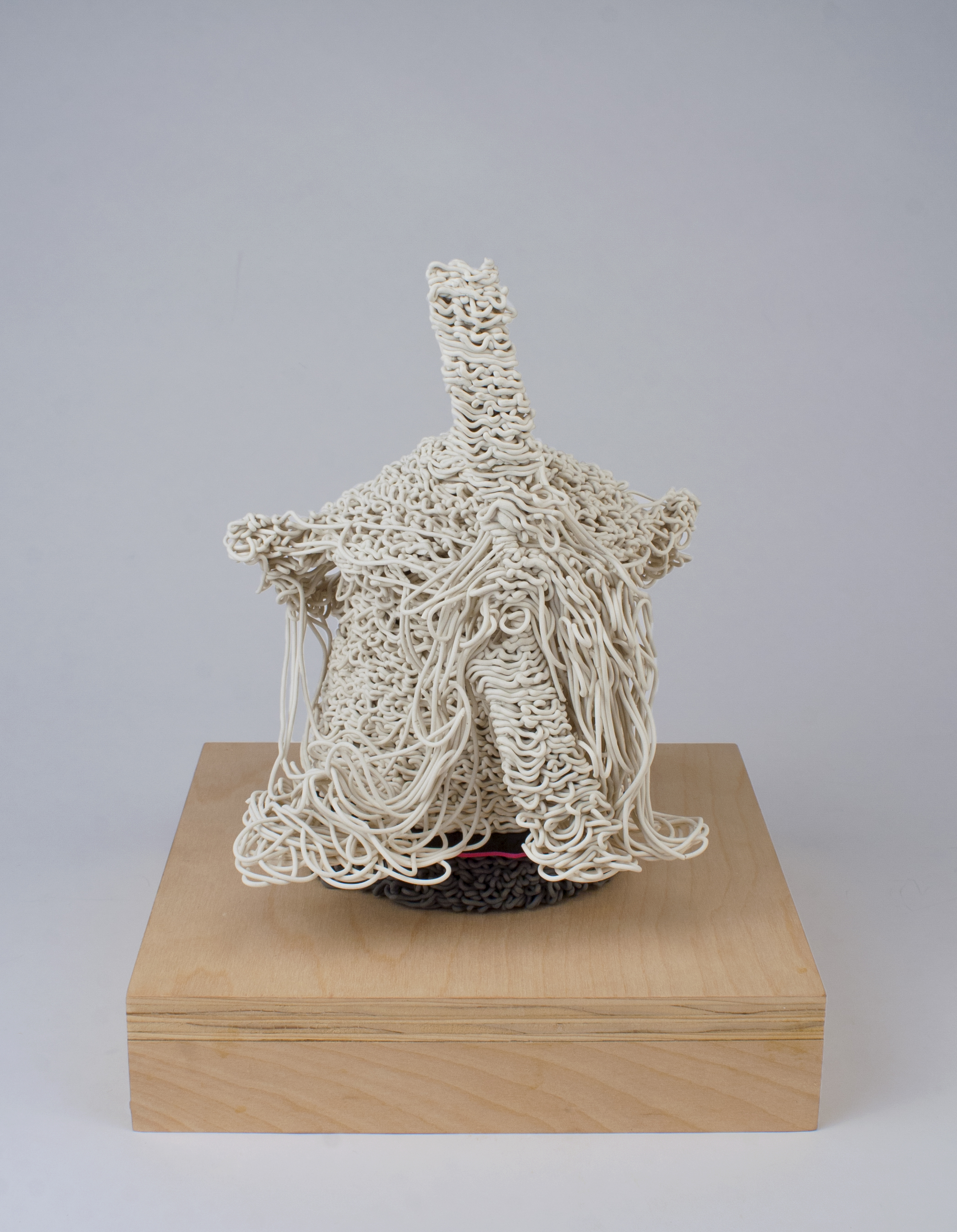

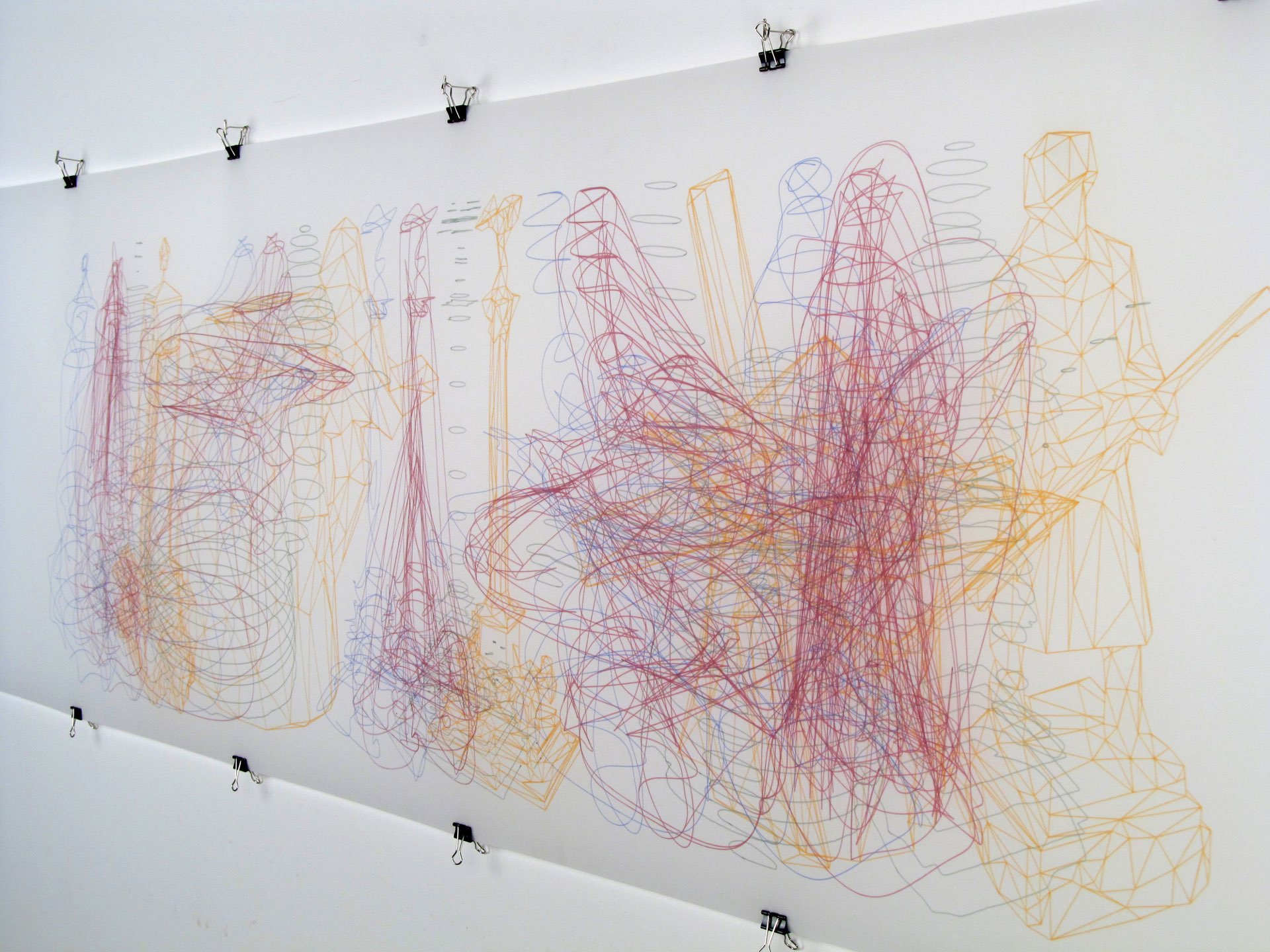

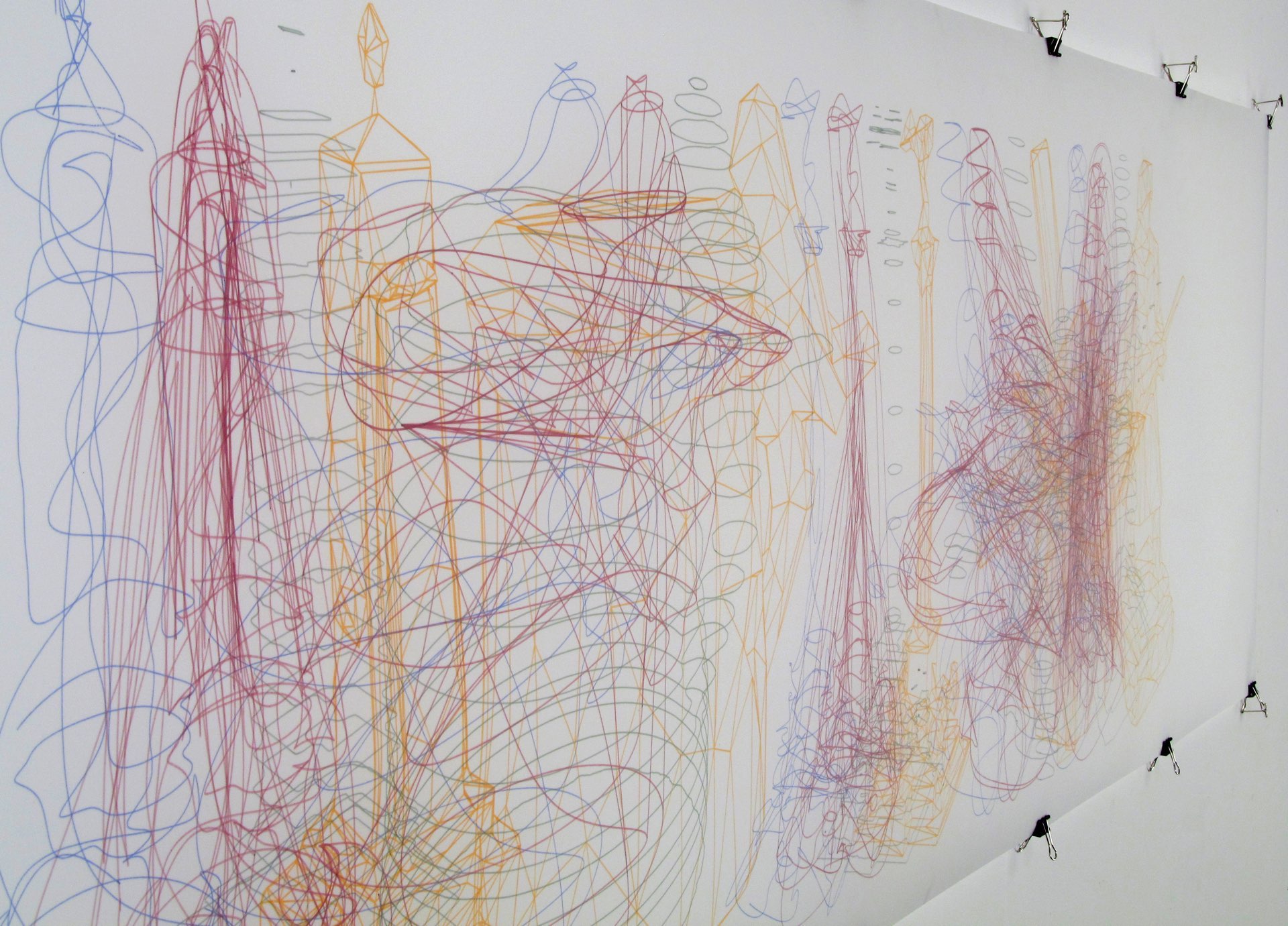

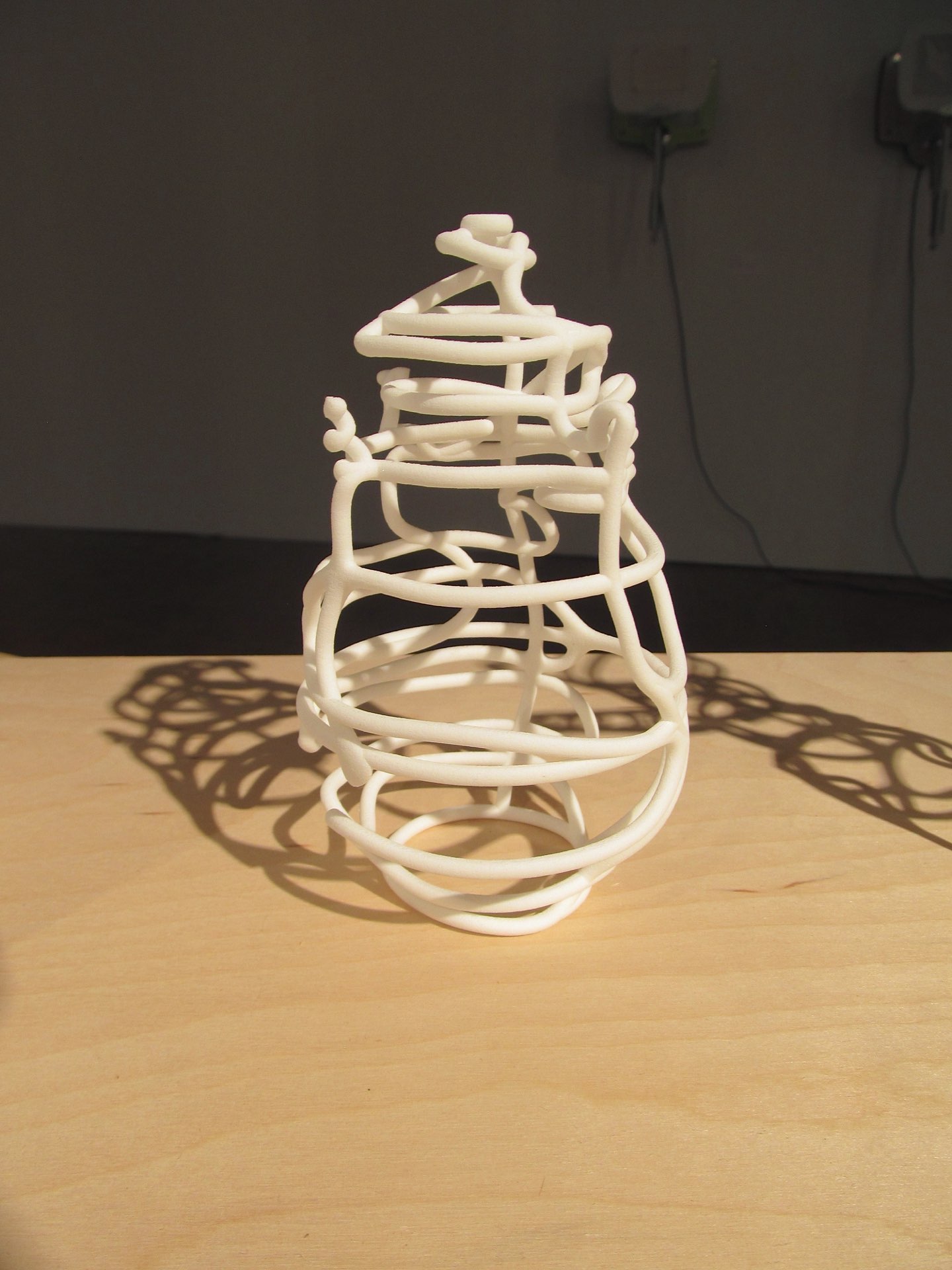

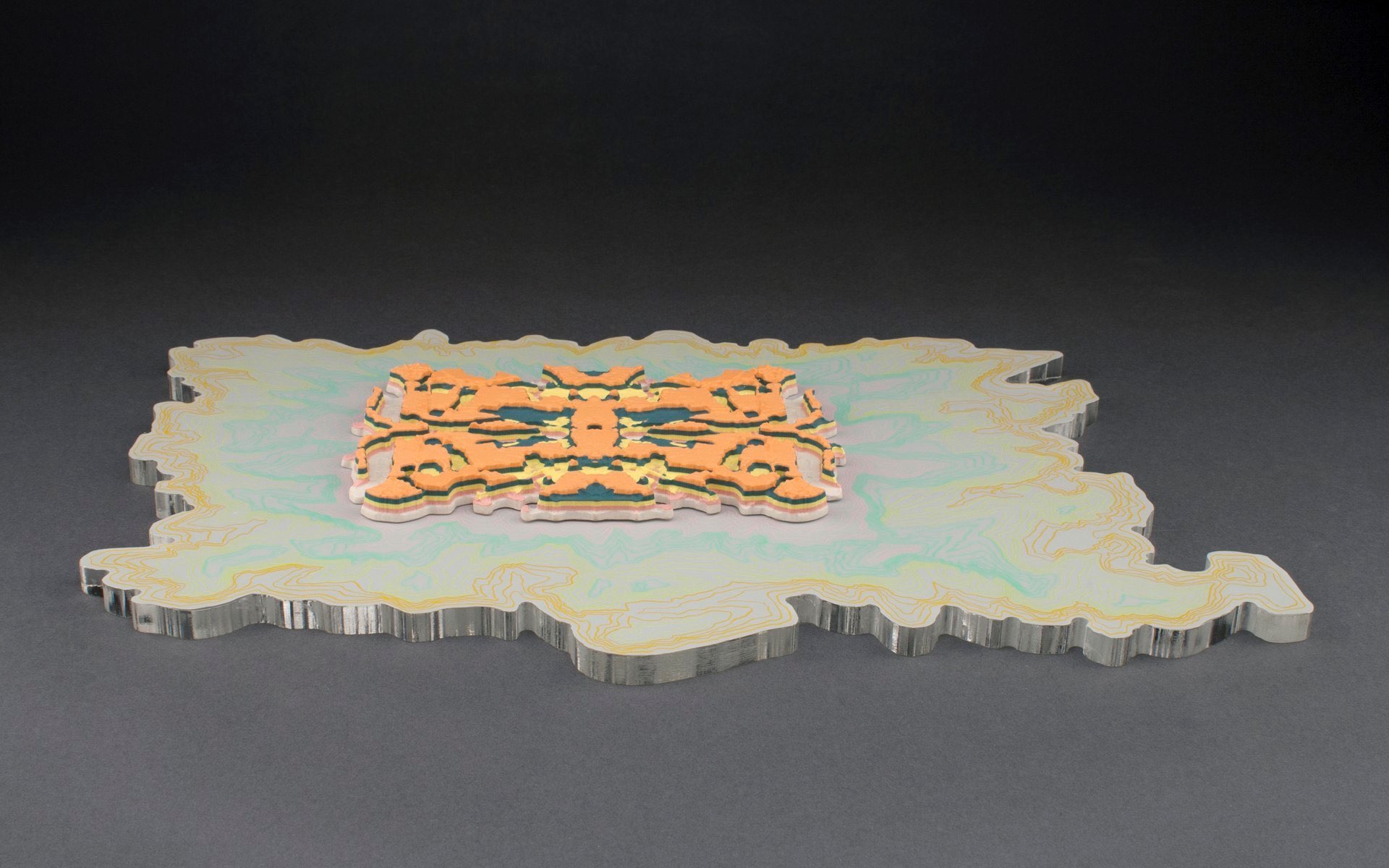

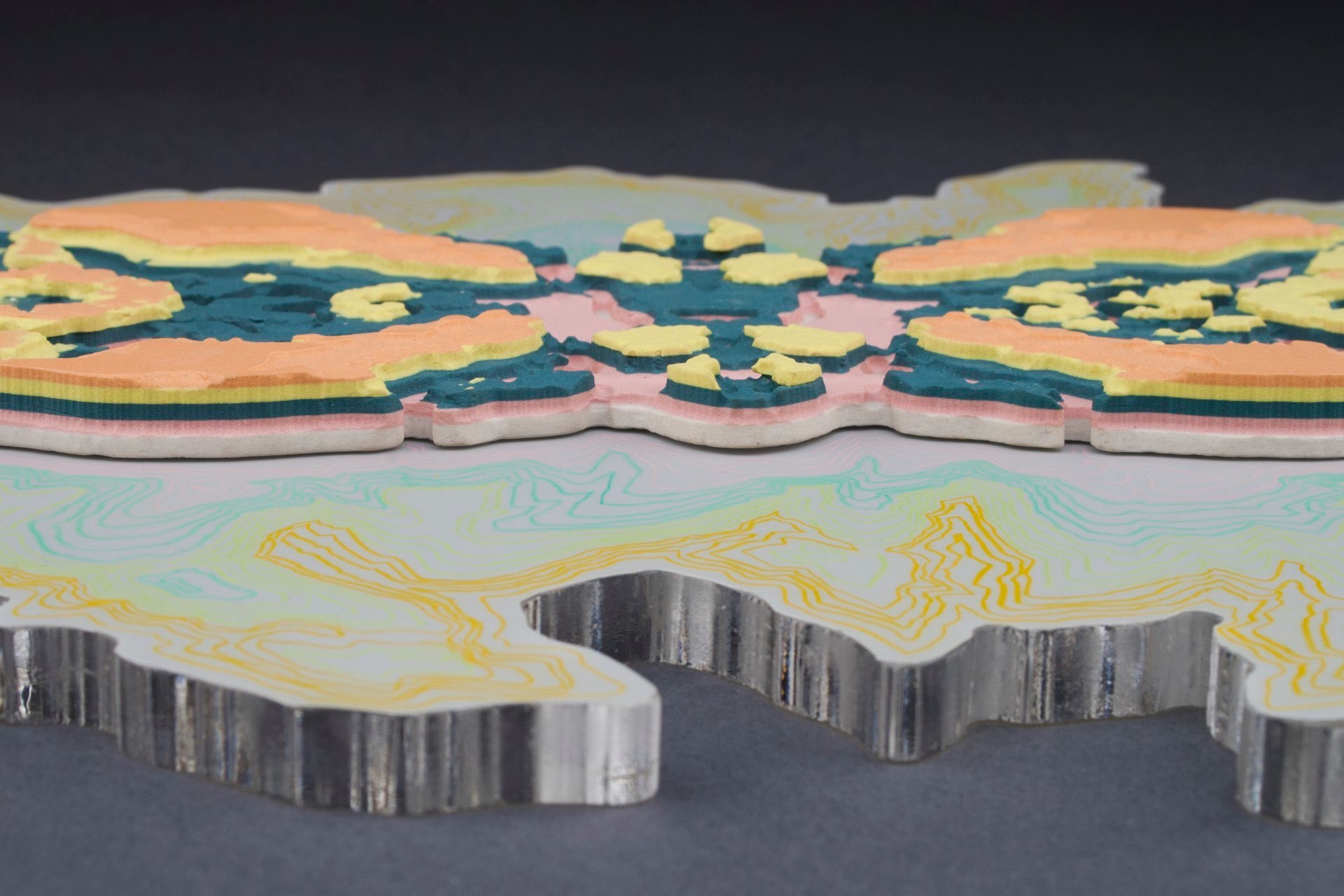

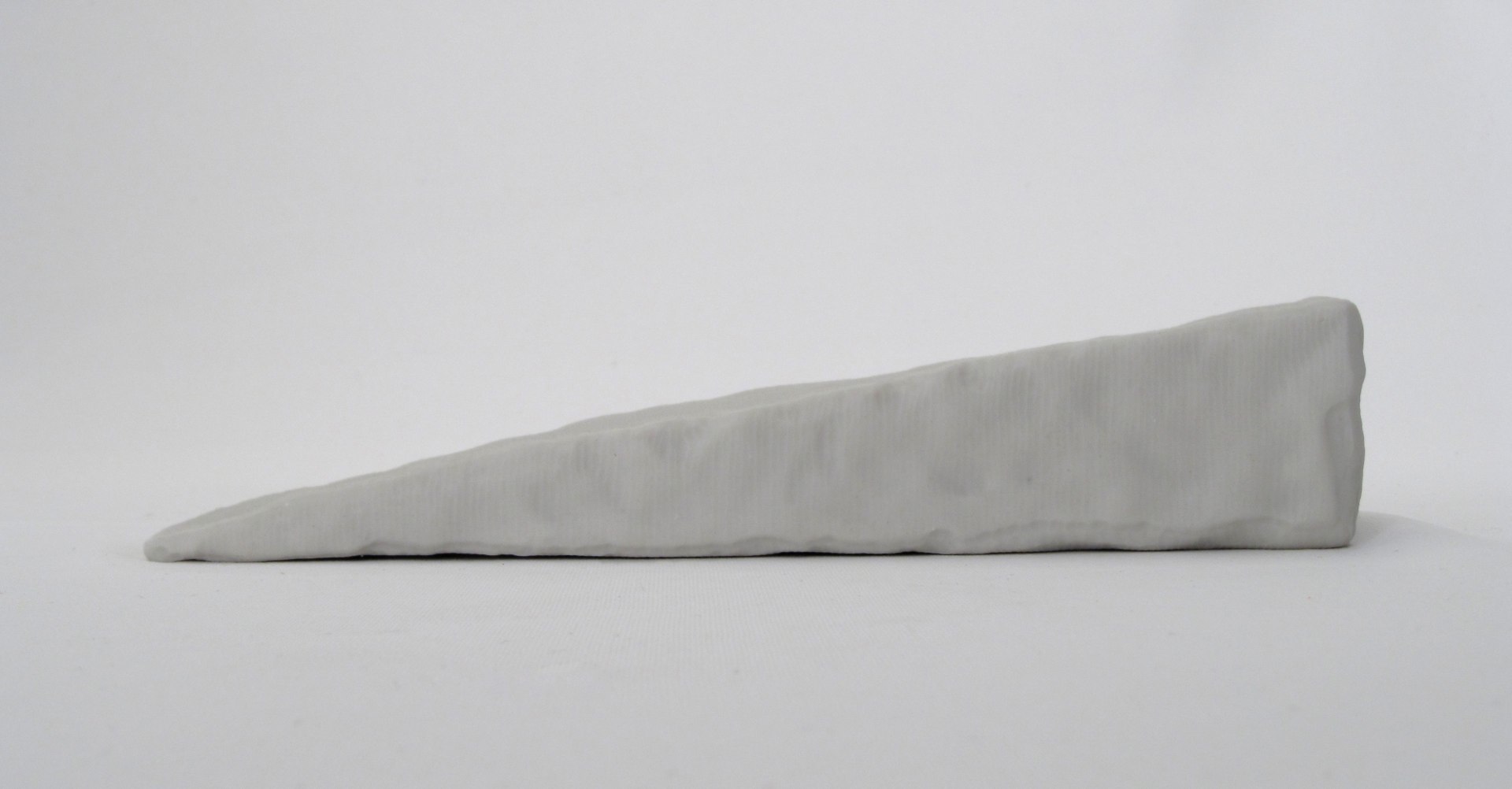

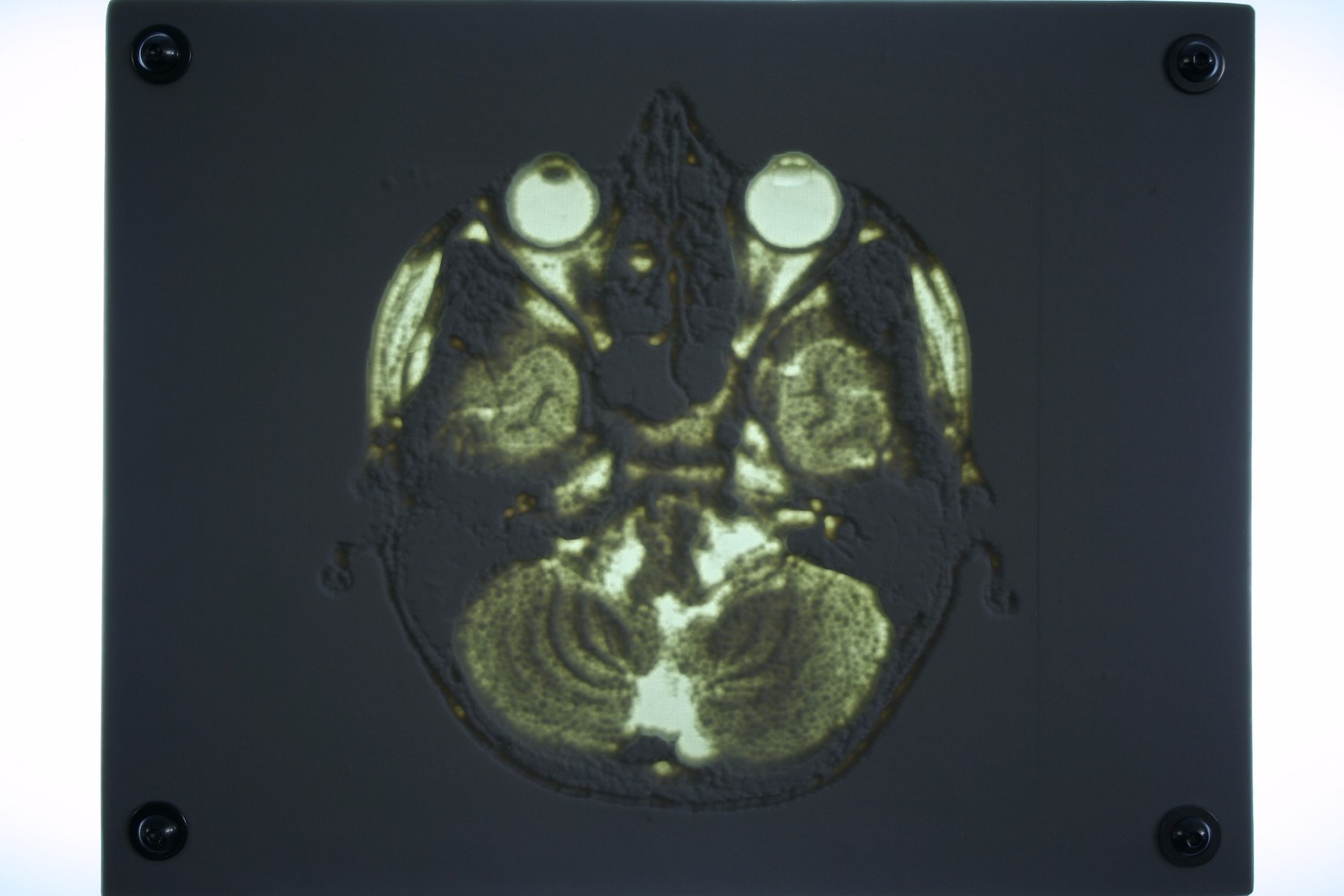

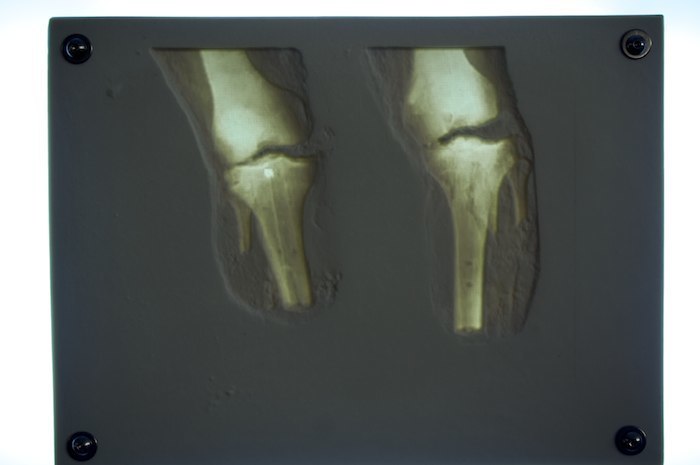

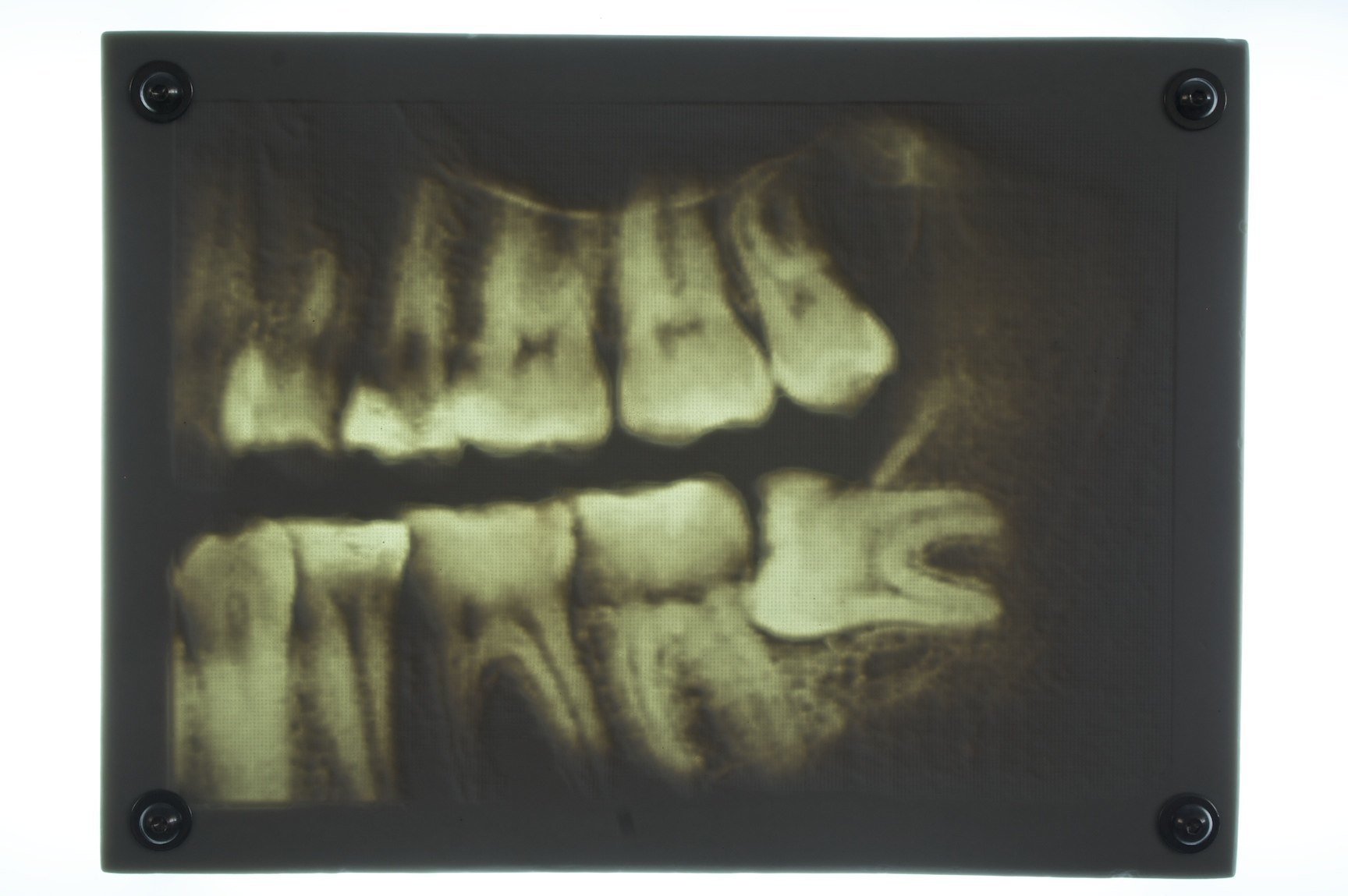

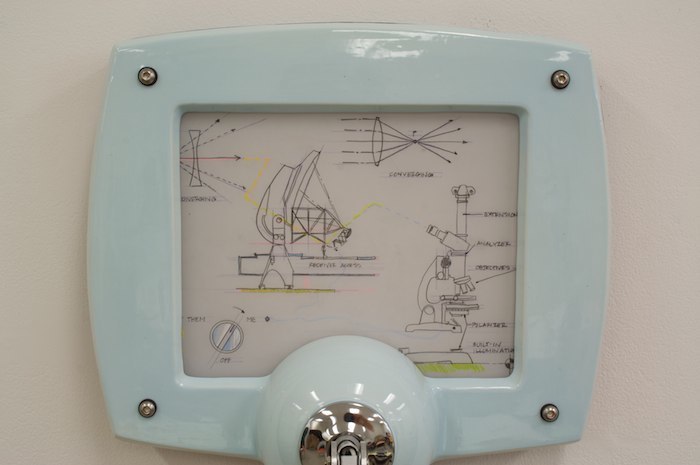

What does it mean to conceptualize of and interpret history from the perspective of both object and object-maker? For viewers, it might be helpful to start in the inner workings of a 3D printer. Bryan relies on digital technology for both the scanning and printing of objects, using images and an algorithm to translate an object to image and then back to object again. When an object is scanned, it stays still as the computer utilizes photos to create spatial relationships between points, looking at both the object itself and its surrounding context. While most artists would take this information to reproduce an object perfectly, Czibesz is interested in the information deemed unnecessary, the oft-ignored artifacts that this software can leave behind. These “little erratics” as he calls them, might stem from data captured from the background rather than the object itself.

Juxtaposed against the seemingly useless information that forms the “little erratics” are the objects that Czibesz scans and reproduces. Inspired by monuments and souvenirs, Czibesz mines his personal and family history, scanning and documenting everything from the Soviet War Memorial in Budapest to a small, china painted, porcelain mug that belonged to his father’s cousin. In the case of the Soviet War Memorial, Bryan’s scanning and (mis)printing of the object allows for a transformation of meaning and new understanding of a historical monument. In the case of the mug, which features a bird on the handle with broken wings, the re-making of the object monumentalizes something feeble and small, allowing it to endure beyond its physical limitations.

Rendering these scanned objects nearly unrecognizable in his alterations, Bryan Czibesz’s work continues to interrogate our relationships with objects. Whether it’s the discarded information of an algorithm that’s been visualized and printed and fired into permanence, or recognizable forms printed in scribbly lines, Czibesz reminds us of the complexity of the term “handmade.” While “the mark of the hand” has been accepted as the signature of an unalienated maker, what does that mark look like? Czibesz’s work asks: if we are to have a sophisticated and intentional relationship with making and tools, how could we possibly reduce that to a mere fingerprint? Instead, we find the “mark” of the maker in the context of the objects, the altering of the tools, and the little erratics left behind.”

M.C. Baumstark